A Place Between Paths

Spilled oats, futility, and regeneration (plus some humiliating marketing)

I farm for a living, if you could call it that. As of late, I’ve begun to doubt if I should. It must’ve been much cuter when we were fresh-faced and green, tender and unstung by the brambles which claw forward upon these claustrophobic pasture lanes. Earnest if not naive, like the once exciting, fresh notion of “farm to table” eating, promulgated by soft-handed consumer-media theorists like Michael Pollan and bloviating hucksters like Joel Salatin, my youth and exuberance and damned hopefulness could at once be charmingly plated and sold at an exorbitant rate. Now, with an additional decade of experience under my belt, now that I somehow know what I’m doing, I feel less like the tantalizing, locally sourced haute cuisine featured menu item, and more like a desiccated turnip rolling around in the bottom of a wholesale veggie bin– at once pitiable and unsightly, a bit of agricultural cull on the killing floor of a commodity food economy dressed up with hollow altruisms and the apparent best of intentions.

In a decade, I have become a much better farmer. The land we steward has recovered from those early, degrading cascades of mistakes and mismanagement I once made. I have become more efficient, more focused, more skilled. What we produce is of a higher quality, we have possibly turned back the clock on some of the broken ecology of this landscape, and we’ve managed to feed many people. But, the economics are fraught, and as my bones ride nearer each other on the ever dissipating structures of their worn-down cartilage, so too is my body. Our farm is a lease, with no current legal path forward to receiving back the equity we’ve built in it beyond selling the infrastructure. My resume is blank from 2011 onward. Having never believed in the notion of credit, I have none, and the market for local and sustainable food which, for a moment, surged in the early days of COVID, is now wilted like that turnip, which is me, relegated to the compost bin, a brief glimmer of potential made null in an era of inflation. Woe!

Yet daily, I return to the fields in which we formed these dreams, borne of rooted earth and spilled blood. Mostly because many things would suffer needlessly if I didn’t. I tally the day’s expenses as I scoop grain from barrels to buckets and on throughout a landscape throbbing with flesh and fat. I come face to face with the impacts of my management, paddock by paddock, noting where the grass is grazed short and the soil bleeds through. This is not work I can easily compartmentalize, as one might with a regular 9-5. Some corners of these fields have become populated with ghosts I helped create, and in the wee hours they visit me, along with mosquitoes.

Year after year, I seek new customers, new contracts, and I do my best to maintain some integrity while conforming to cultural food fads like a chameleon– from worn earth and weeping sweat we conjure products as raw as our wounds, and dense in nutrients too, nearly as dense as the suckers who allow themselves to be mystified by organ meats and caveman diet schemes trotted out for their insatiable maws by cynical swindlers and con-artist influencers. The humiliation only ends with a check in hand. How did we get here from what were once such honest concerns about the state of our environment, our economy, and our food system?

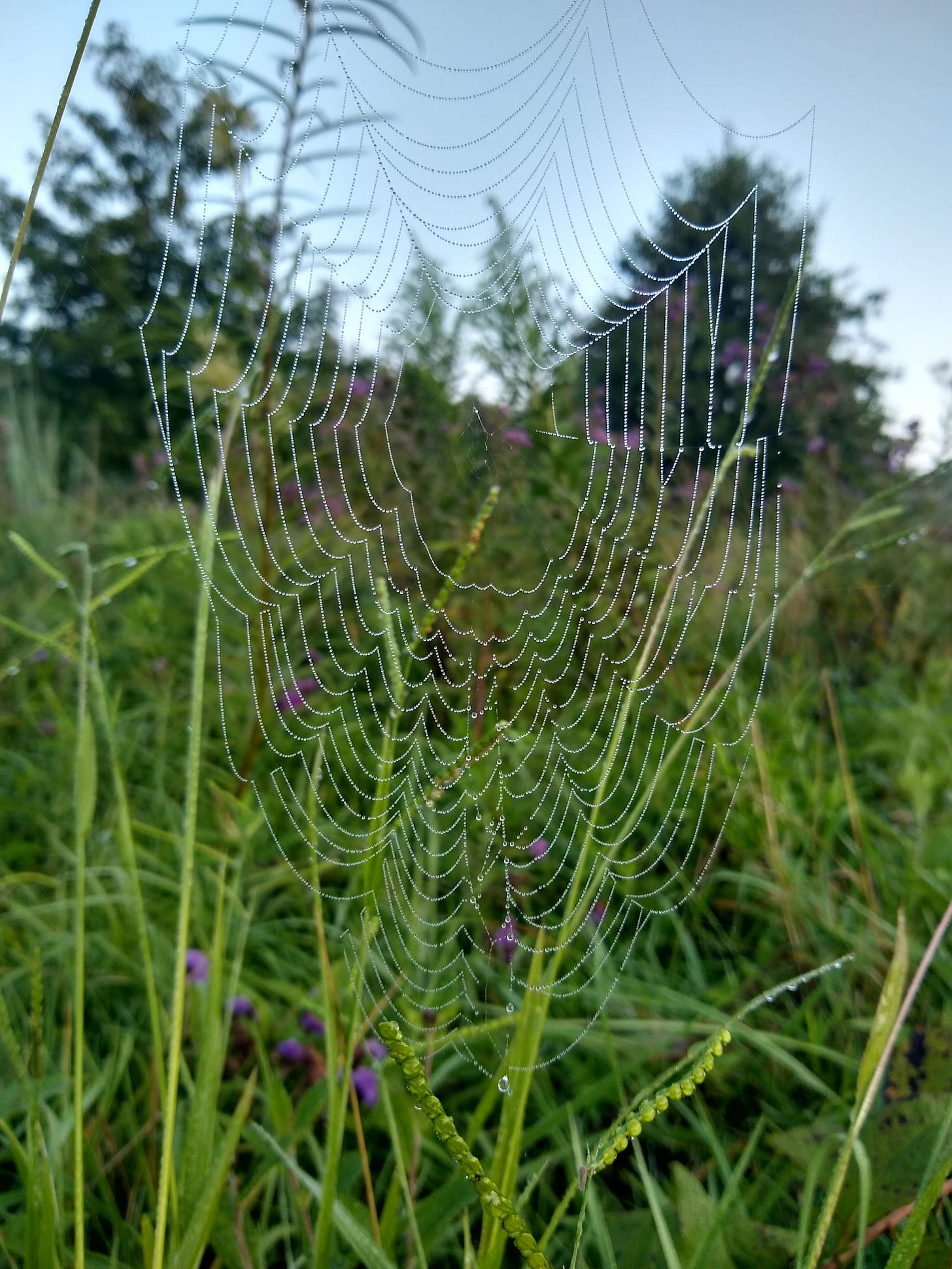

Now in late summer, with the prairie at near full profusion excepting goldenrod and aster, our fields, from a bird’s eye, appear cracked by the intricate traces of paddock lanes and walking paths. As the tallgrass enters its photosynthetic crescendo, its fat stems splitting with emergent blooms shining from birth, and the patterns of our grazing wind symphonic through the chess board of prairie swards and broad saddles of resplendent ironweed and fading bee balm, the complexities of multi-species grazing on a finite and intensively managed pasture make for a once unified landscape that is now cut through and shattered by a web of linear clearings. Lines– the telltale footprint of the colonizer, the parceling and territorializing of bridled wildness into boundaries of property and economy. For all its potential, the world of “regenerative” grazing does ultimately come down to boundary marks and lines on a map, a far cry from the original generative processes by which these riches of earth were initially born.

Some paths and lines lead out to the herd of nanny goats, clearing invasive autumn olives on the broad and windblown shoulders of the slope. Others lead down to the white oak and osage bottomlands, populated by heaving, snoring swine and armadas of dragonflies on the hunt. Well-trod cart paths are stomped down each dawn at milking time, and at dusk we herd our turkeys back to their shelter by way of narrow, claustrophobic traces, obstructed by the razor whips of multiflora rose and bristly limbs of weathered red cedars. Some paths lead to eaten down paddocks, cleared of summer vegetation, but burgeoning now with bright young crop of autumn mustard and newborn clover. Some lanes lead us to nothing but ticks, and in the end, they all fade as the prairie grasps for the dwindling rays of late summer.

Each pathway seems to lead towards some vain labor, and we are careful to not overly fragment the landscape, if for no other reason than to maintain as much forage per acre as possible as we graze into the photosynthetic contraction of autumn. This past week, this arrangement has left me awkwardly hemmed in during some of my labored ambulations. To reach the growing pigs and turkeys, I must move through a series of three gates and cross a rich, broad, unmown area. To the south of this space are a group of cows, and to the north a pair of largely docile, if hulking, boars. This place between paths is breast-high in agrimony and tick clover and seething with seed ticks, chiggers, and oak mites, not to mention the brambles. It also contains some of our lushest clover– rather than further fragment this shard of excellent pasture, I tromp through, suffering the scratches and sticker-vines and parasitic risk to reserve a wee bit extra forage for our stock as they prepare their bodies for the dwindling wind down of summer.

The world between is unwelcoming, at least to my economic activities. The axles of carts and wheelbarrows become wrapped in grassy tendrils, jamming bearings. The low-lying canes of dewberry, prickly and whiplike, scratch at the flesh. Tick hordes quest on the tips of springy, thick stems of grass, and at least thrice daily I struggle through this tangle to exchange a calculated dollar amount of feed for the flesh and fat that will again become currency, the absurd ouroboros of modern farming— resource extraction in exchange for financial abstraction.

Struggling in the sun with a barrow-load of sprouted oats and water, my wheel hits a rut, long ago torn into the soil by poor judgment and heavy machinery, a line no longer imaginary on some map, but an eternal scar upon the earth, made in thoughtless haste in this place between. The wheelbarrow capsizes, and the water, plus some dollars-worth of oats, spill into the compacted trench. Naturally, I curse, and then I sit down in the creeping wilds and let my form recede into the brambles and forbs while a tension headache sets in.

I came to the ends of these paths in an attempt to evade a system I learned was destructive, to find usefulness in the tending of soil and gentle provisioning of food for my home and community. But there’s no economic efficiency to be found in this work when performed at such a small scale, not while still living very much beneath the bloated, corrupt beast of capitalism, that which mines all to the core with a death urge and subjugates us into debt modules and commodifies those resources which once remained our common right and responsibility.

Between two paths– get big or get out. I sit in spilled grain a moment longer, rise, and press on where no lane leads. I can’t pause long to cry over the spilled oats, nor the misdirection and lost revenue and time. The stock and soil must be cared for, and I try not to forget how great a privilege it is to have access to land, with or without equity. Even here, where the original topsoil has been stripped and sent asunder to the Gulf of Mexico and the hills are stricken with suffocating clay, I am extremely privileged, and I need to make this privilege count for some good in the world. But I bristle at the notion of forging a new path, drawing a new line, as my race has done since its occupation here. Instead, I trudge this place between.

When we label the systems by which the world is fed, such as regenerative agriculture, the sensible, understandable tendency is to provide a measurable definition of the descriptive practices– cover cropping, no-till, intensive grazing, etc… I do think this is important, so as to not mislead or greenwash. In fact, a reasonable critique of permaculture as a design system could be that there isn’t necessarily a clear checklist or data-point requirement in determining whether or not someone is “doing it right.” Still, I think to make the bold claim that our agriculture is “regenerative”, if that word means what I think it means, may well require that we quantify how our work heals more than the soil, or repairs ecosystems. The true practice of regeneration might be the healing of socio-economic wounds in addition to the ecological, because the nature of extraction and degradation of land applies equally to cultures and communities. Perhaps we cannot repair what hurts under a system of harm, without stopping the harm itself. Perhaps we must get big, and get out.

I didn’t choose an agrarian life because I thought it could solve the world’s problems. I chose it in part because food is my love language, but mostly because it’s long hours outdoors without other people. I am hesitant to mow a new path or draw a new line in this enterprise, because it may likely put me inside of well-populated rooms full of people I need to ask favors from, instead of being out here, wallering in the brush, grasping at handfuls of spilled oats in the prairie mosaic. I may be familiar with ticks and fleas and lice, but the potential level of parasitism involved in the “do-gooder” sector is truly creepier to me than the brambled, snake-strewn thicket I currently reside in.

Pressing on and bleeding ever-so-lightly, the hub of my wheelbarrow choked by briars, containing a payload of the resources I could salvage, I finally arrive at paddock’s edge, and the barrier of wire-embedded plastic poultry netting that contains our turkeys, at least for some hours of the day. At the edge of these bottomlands, where the menagerie of budding goldenrods and sprays of boneset terminate into the cool darkness of oak shade, a flock of thirty turkeys kicks through the duff in search of bugs and seeds. Stepping over the fence until it is quite out of view, I watch them dance and strut and meld with the savanna, without invoices or processing dates or backlogged inboxes in my field of view. This place without paths will be fine for now, at least until I need to head back home, and fix some afterschool snacks for the kids.

On that note, I must necessarily further humiliate myself a little more and perform some grovelling— I am taking orders on fully grassfed/finished beef, if you’re in the Northeast Missouri - St. Louis - Columbia region. Email me for details. We’re also opening up for reservations on autumn/winter turkeys and pork, and planning out another butchery workshop for this November— details to follow. And if you’d like to connect in a decidedly less consumerist way and you’re in the St. Louis area, come visit us at City Greens Market this coming Sunday, August 24th from 11 AM- 1 PM. We’ll be demonstrating some fermentation basics. If we had more markets operating off of City Greens’ food sovereignty model, I’d probably complain about my job less…

CORRECTION: We will see you in STL on Sunday the 25th, not the 24th. Oops.

Joel Salatin may often be over enthusiastic and hyperbolic sometimes but a huckster he is not. God bless that man!