Between the Wire

Fear, control, and fencing

In the dust dim morning light, scraped coyote hair flits in the wind of the field, snagged in rusted fence-wire. Winding along a waking slope of cow pasture, green and warm and smelling of the stink of spring, the wire sags and oxidizes near where the grasping claws of gooseberry and rough stems of pin oak have sprung from trodden deer paths. Stride by stride, the thin prison of wire stretches to the road, where it meets the weathered hedge posts of other fences, other fields, the fine dust of spring tillage choking the sky and clothing the trembling cottonwood catkins in pulverized earth.

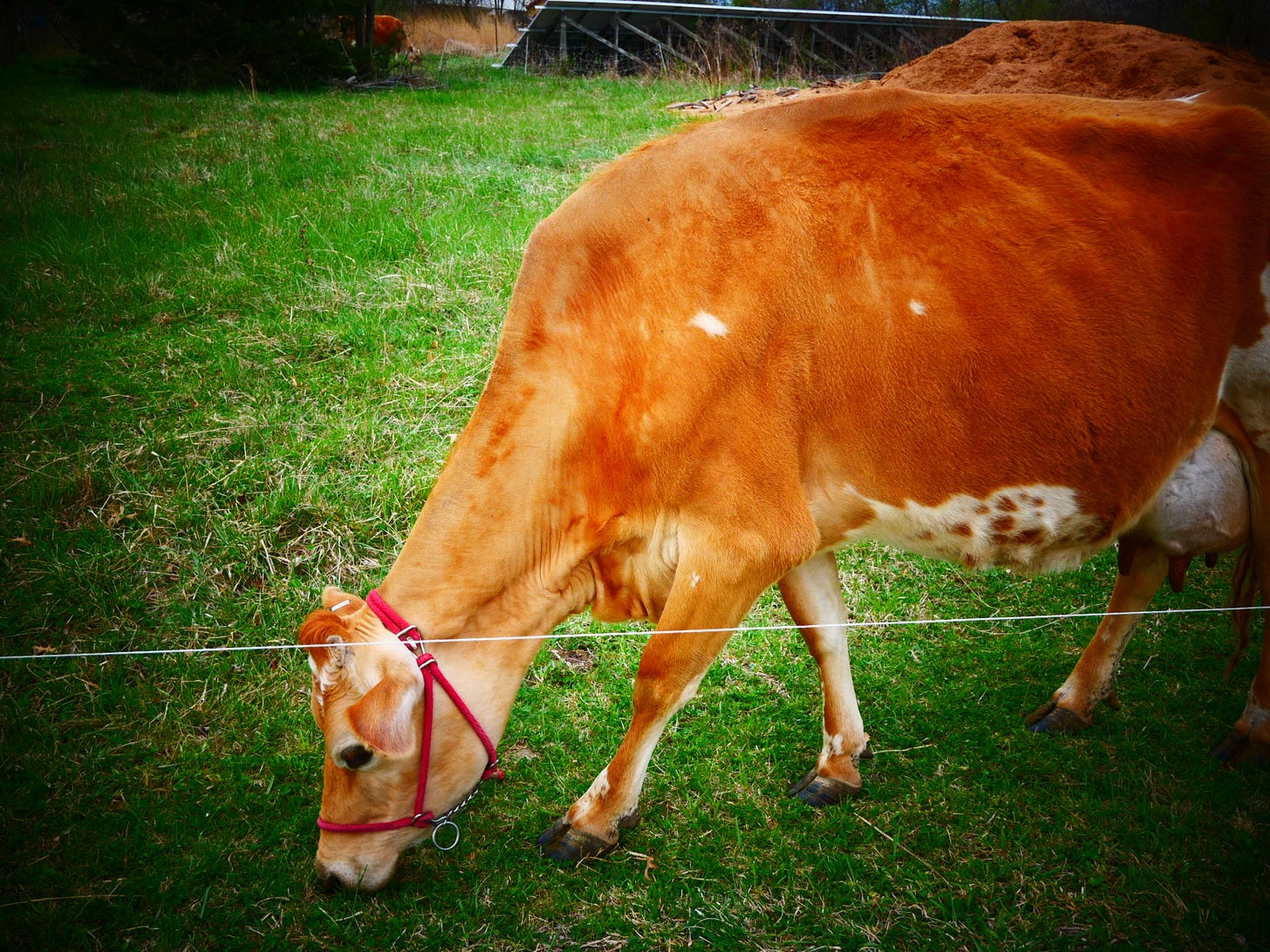

In the shadow of the filthy sunlight, goats and cattle, patient but insistent, wait for new pasture. We hold them with portable electric fencing– a manipulable apparatus constructed of fiberglass and plastic and metal, rare minerals and electrons, and to a degree, fear. We like our fences hot– a hot fence leaves an impression, facilitates human control (to either the benefit or detriment of the land and stock), discourages predation, and helps me to sleep at night. I’m unsure if fear is really the right word here. Touching an electric fence stings, and the animals don’t like feeling it, but it isn’t as if they exist in a state of constant paranoia– our cows are merely cautious as they crane their muscular necks beneath the single strand of wire to chomp fistfulls of green grass just outside the range of their paddock.

In spite of the material construction and embodied energy of this technology, namely plastic embedded with conductive wire, hooked to a solar-powered energizer with a small 12 volt, 12 amp hour sealed battery, we can manipulate the cycling of solar carbon and organic matter, negotiate the exchange between habitat and sustainable food production via controlled disturbance, and raise nice, healthy animals. We can leverage grazing and browsing against troublesome plants like autumn olive that threaten tallgrass ecosystems, or we can totally destroy it, based on any number of factors related to stocking density, weather/climate, or duration of graze, but the single most important factor is probably the mindset of the person operating the fence.

In the early days of the pasturing season, when the grass is slow to become thick and fat with spring rain and warmth, the animals all need to move quickly. If we don’t do our job well as herders, if we don’t move them in a timely manner, they bawl and loaf at the fence-edge, sniffing the sugary air. The flipside is leaving them on a paddock too briefly– they only eat the “candy”, so to speak, and leave behind less desirable plants, sometimes leading to a potential pasture composition balance later down the line. In a multi-species grazing project there’s no day off from moving electric fencing, at least between April and November. A fence is made of electrons and wire embedded in plastic, and plumb, firmly planted posts, but the best ones are ultimately built from fear of being zapped– though from time to time, hunger makes any low point in the netting “goat operable”.

We try our best in grazing to hold a balance– between running our herd hungry and coddling them, undergrazing and overgrazing, between cautious stewardship through animal disturbance and extraction and degradation. I’d like to think that in our case, portable electric fencing is a tool for regeneration and care, and perhaps this is true. But I also have to acknowledge that the primary function of this tool is control. Whether we farm in the basic agri-industrial sense of obtaining a suitably high-yield from a piece of land in accordance with the economics of the day, or if we attempt to practice an agriculture that is more harmonious with our surrounding ecosystem, we often resort to leveraging control –of the movements of animals, of the placement and distribution of resources, of mechanical advantage from the simplest implements to increasingly advanced, fossil-energized machines– towards the ultimate goals of feeding people and fiscally holding onto our ass for another season. I have seen cows in denuded feedlots kept in by sturdy steel-piped fencing, clopping in their own shit as they gulp down grain distillation byproducts from ethanol production, and I’ve seen them play and graze on waking prairie, belching and lazing among the Speckled Fritillary butterflies, freckled with elm seed, a single thin strand of hot-wire offered more as guidance than imprisonment. It isn’t the fence that separates these approaches, but the fence-builder.

In a late April dry spell, in the days and hours before a rain, when the wind picks up and heavy low clouds billow in, there is a certain hum, a slight whine or whirr of bearings and clanking hitches and scraping harrow teeth as farmers prepare and plant the broad flood-plains with corn. Storms of dry topsoil are heaved aloft as the planters rumble and whine, and vast clouds of earth drift over the roadways in squalls. Even up here in the hills, where no machine can be heard above the songs of meadowlarks, the sky becomes hazy with silt.

I walk along an unfurling hedge, where the remnant trees of seeds carried to corroded wire by generations of birds and rodents are reaching up over the ridge-top– wild plum and chokecherry, fuzzy grape buds, and sensuous autumn olive blossoms all breaking and thriving in the middens of the rotten fencerow. A few stubs of rusted barbed wire remain forever wedged in the thick crotches of Osage orange, and the catkins on the cottonwoods wiggle in the dust-laden sky. It’s a part of my regular walk out to the orchard, where we’ll soon be busily planting hickories and persimmons and oaks before the next spring deluge, in much the same way as our corn and soy growing neighbors.

I check on the burgeoning young chestnuts, at repose in their shelters –6 foot tall plastic tubes anchored by durable fiberglass rods– lifting up their protective prisons to get a look at their vibrant spring bark and fattening buds. Again, fear is the tallest fence, so I let my dog run after deer and hunt down voles in moist mulch piles and brush while I inspect our young crop. We recently mowed an acre or so of dormant prairie adjacent to the existing trees to make room for more of this “gentler agriculture”. With a muscular flutter of wings and a staccato shriek, an anxious woodcock pumps her way to safety from the sliced down thatch, revealing her destroyed nest of four bloody, broken eggs. The air is chalky, the birds grow quiet, and standing over the smashed brood, I can hear the distant whine of planters. This is where the leverage of control, of energy, leads us sometimes.

The woodcock population on our land is very healthy, and I have no doubt that in the larger scheme of our stewardship, the loss of these four eggs is but an unfortunate blip. It could have been a raccoon, or a dog, or a heavy rain that killed the eggs, but the sight of the hen, mourning and fearful, hasn’t sat well with me for these past few days. It is the cruel, early spring. The turkey hens strut anxiously about our slope, driven by a deep instinct to nourish and protect their hidden nests. Little ducklings are waddling out from beneath sheds and wagons, and chickens scratch and coo at their chicks, beckoning them toward fleshy crops of dandelion that protrude stubbornly from their fenced enclosures. Sometimes, the little birds are lost to predation, and in the larger cycle of the season, there’s perhaps some order to it. But there is some difference between this and the cruelty of men. Standing over the bloody nest, I cannot help but think of the cargo plane loads of mostly young men being shipped to El Salvador right now, and consider the heinous and pointless cruelty of the action. I watch mother hens fluff their breasts in the wind and dust, tucking their chicks beneath their wings, and I don’t care what those young men may have done or been involved with– they’re still someone’s babies, and now they’re lost.

For better or worse, fear is a part of this landscape, as my dog runs off every visible animal nuisance. I’ve been able to leverage sensory cues –barking dogs, human urine, rotting effigies– to discourage pests that would otherwise damage or destroy our crops, with some success. In their world of relatively free movement, the cottontails and deer and voles are encouraged to seek other adjacent habitats overtime. We are even playing with the idea of mounting raptor roosts and kestrel nests near crops that sparrows and other foraging birds would ordinarily decimate. Under these circumstances, a moderate application of fear can be used to delineate a necessary boundary. Even applied by a human farmer for the purpose of protecting a largely anthropocentric crop, this ordinary, natural fear is, if not explicitly harmonious, not purposely cruel.

The purely human, political landscape is different. We are subject to cruelty within cruelty, and fear within unnatural fear. We build and maintain and fund what are essentially black sites, for the displacement of people we cannot easily see, nominally for the safety of our wider society, blind to the fence we’ve so neatly and efficiently erected around ourselves. The resources may not exist to lock all of us up, but it would seem that those in power would like to see us all imprisoned, if not physically behind bars, then within our own fear. My dog, panting, returns to my side after running off cottontails, and we walk back from the silent slope while the dust mingles with sporadic raindrops.

Some people say the best time to plant corn is when the oak leaves are about the size of a squirrel’s ear. Personally, I like to wait a couple of weeks after the conventional plantings are done, because I don’t have crop insurance, and our clay soils seem to stay cool longer. If one is not familiar or tuned into all the types of big implements whining through the countryside, they can head to the right cafe (Zimmerman’s if you’re in Rutledge, Lacey’s if you go as far as the county seat), and you’ll be sure to hear the question “Didja get your corn in?” uttered.

Preparing for a rain that still has not arrived, I spend an hour or two in the afternoon planting some hardier seeds in our garden– plump, sprouted peas and sunflowers, kale and collards and lettuce and beets. Over the years of tending gardens and building fence, we’ve gotten okay at excluding rabbits and other forms of varmintry, but from all directions, tough-rooted perennial weeds– running grasses, woody brambles, resolute chickories and dandelions, all inexorably creep and tug at the steel and wire boundaries, their tendrils deeply entwined, determined to invade the beds and take advantage of the plentiful water and fertility. I can spend a few moments every day on my hands and knees around the perimeter, tearing and uprooting them, but by the time I’ve tended to every foot and inch of the garden fence, new growth has crept back into place where I started.

This small plot of land was once tied in all directions by field fence. It is largely gone now, save for the generations of tree seed that has sprouted from the sparrow shit of it’s own skeletal remains. Someday, I suspect this garden fence will be much the same. Whether out of cruelty or a simple need for control, the fences we build all crumble some day– perhaps we could stand to be more like the weeds.

Some of the nanny goats are at the edge of their fence now. They haven’t begun to bleat, or test to see if it’s hot, but they’ve eaten all the candy grass in their paddock. I’d like to see them strip more bark from the autumn olive. Perhaps they can go another day in their fence. Walking past the paddock, the nannies return to the shelter of dusty cedars, and ruminate nearby the gang of playing kids, who take turns between bounding acrobatics and tender nursing.

As the dust billows and the clouds creep and the wild plum petals flit on the breeze and collect in the depression of the abandoned woodcock nest, the turkey hens are skulking through the brush to find somewhere safe to lay their eggs. Over the years, I’ve lost hens, eggs, and even young turkey poults to predation, because broody turkeys are so insistent on setting nests in places that they feel safe in. I can’t always find where they’re laying right away, so this year I have built a few purposeful brushpiles in safe locations to entice the hens nearer our livestock guardian dogs and away from the potential peril of foxes and raccoons. I’m also keeping enough portable electric netting on standby to safely enclose any turkey nests once I find them, but in my years of raising turkeys, I have not generally found a way to reason with these birds– especially when they’re anxious or fearful.

In the end, I suppose the whole damn thing is out of my control really. The rain I need is pushed back by the breaking rays of sun, and I can see one of the turkey hens strutting well out of safety, or at least my own control, among the violets and chickweed and cleavers in the thin cover of broken branches along the creek bottom, while futile volleys and plumes of displaced prairie earth whirl along the slope from the plowed out river bottoms. The autumn olive is in full bloom, the running grasses are creeping through the chicken-wire of my garden, and as the limbs of old hedgerow trees come alive with swollen buds and sunlight, I find myself seeking out some deeper shelter in this uncertain place between the rotting fence.

Another beautiful post. I learn so much reading your work, how intimate you are with your land and its creatures. And yes, fences and fear are being strung around and between us. Kindness and courage needed now more than ever.

Thank you, from far away Scotland, for an interesting and insightful read. I’ve adopted the term “loafing yard” of yours to refer to our kune kunes home run.