From the Archives: Bitter Harvest

Solidarity, Self-Subjugation, and The Wheatland Hop Riot of 1913

Dear reader: This morning while working on moving pig paddocks and falling behind on what will be my second annual Labor Day edition of the almanac, I came upon a winding, twining thicket of wild hops, bearing its ripe cones, down in the walnut and sycamore bottomlands. Knowing that I’d be unable to finish the next entry before my intended goal of sundown tonight, I felt inspired by this sight enough to dust off this old piece and present it to some new readers, as well as those who may have forgotten it.

What follows is a chapter from the almanac published last year that I have resurrected from behind the archive paywall for everyone to enjoy. I have gained many subscribers in that time— some of which I’ve even maintained up ‘til now. This was an early precursor to the Rural Discontent series that I’ve provided to supporting readers— the next installment of which will arrive in a day or two (it is taking a bit more research and consideration than I’d originally thought it would).

If you enjoy my more researched works, want access to the full archives (probably about 500 pages of written material at this point), or just want to support me in finding the valuable time to bring the Fox Holler Almanac to y’all, upgrade your subscription. Thank you.

Some day, when Labor’s age-long fight for life and freedom is ended, then will there be a monument raised over the graves of the Wheatland martyrs-and it will show the little water-carrier boy and his tin pail lying there on the ground mingling his blood with the water that he carried, and over him, in a posture of defense, the brave Porto-Rican with the gun he had torn from the cowardly hands of the murderers who had fired upon a crowd of women and children. -Big Jim Thompson

A hot breeze is coasting up our clay-stricken slope this late summer afternoon, swinging the goldfinch-topped sunflowers, rustling the five foot tall stalks of prairie grass, sending plucked clumps of duck down airborne, only to alight upon the desiccated brambles and thorns of the ditches and draws. Though it may be Labor Day, summer doesn’t look to be over from over here on this hot sidehill. Sure, the cicadas begin their whirring chorus later and later in each shortening day, and some mornings are chilly enough for a light flannel, but I won’t be packing my white shirts in the closet, avoiding a nice cool down at the pond, or imbibing any pumpkin spice themed confections for another few weeks. The light chill of dawn evaporates early most most mornings, and as our swine herd rises from nests of trampled grass, the heavy night dew lifts from their lardy figures, burnt off by piercing sun. This week is to remain clear, hot, and rainless; an unofficial end to summer indeed. Here, we mark Autumn not by calendar date, but by the blossoming of the asters. For now, it’s locust season, when growing hordes of grasshoppers spring and tumble in the dense swards of prairie grass, and patient mantises lay in ambush. Mink, woodchuck, and squirrel have all begun to fill their winter caches. There is much to gather, and the days are now perceptibly shorter. It is time to stash, store, and otherwise grow fat for the short cold days ahead. The labor of beasts who must provide these provisions for the winter is ceaseless. Me too, squirrel.

And so for my first considerable break from work today, other than lunch (I consider digestion to be work), I am here on this hill top, in the shade of a sprawling Osage orange tangled in wild hopvine, writing cross-legged on an old folding chair at a lightly shit-specked table the young chickens sometimes roost over, musing upon labor.

Farm work is hard work. There’s no shortage of independent, self-employed farmers, myself included, who stress this fact until it becomes cliche. Maybe we even whine about it on purpose. Certainly, developing a self-mythology around tireless labor and dedication is part of the low pay we receive for growing food, so if others look at our labor in awe, it helps our egos a little. Of course, not everyone finds our labor admirable. I’ve met my fair share of individuals who think I am stupid for performing undervalued labor, or more likely, that they are better for performing overvalued labor. Perhaps they’re at Burning Man as we speak. Still, much of America has a romantic image of the farmer as fierce independent, some human struggling against acres of land and seasons of challenge, and to a degree, this can be true, at least among those in the heartland performing farm labor that primarily encompasses isolation across vast tracts. Still I think part of the myth comes from a very political place of depicting farmers as older and whiter than they sometimes are, because those are the farmers that can and do legally vote, and hence they are the farmers that demand an outsized amount of pandering from politicians during every election cycle.

Not to take away from the very real struggle of this work, but I think the romantic image of the farmer as tireless independent carries with it a considerable blind spot. The result of land conglomeration and corporate enclosure has ensured that labor has increased for the fewer and fewer farmers out there who are tending more and more land than before. This is to say that technology is not leveling the playing field, in regards to labor, it is making the field bigger, with fewer players, even with mechanization, and GPS guided harvesters, and drones and AI crop management software or whatever else the ag tech companies think folks might want to take a loan out for. Still, in terms of intensive labor per calorie consumed or dollar spent, our (literal) whitewashed image of the lone, stoic, toiling farmer pales in comparison to migrant and itinerant farm labor, particularly the labor employed in fruits, vegetables, and meat-packing. I think that most Americans, when asked to close their eyes and picture a farmer, will see an older, white guy in or near a tractor. It’s understandable, as that’s pretty much what I’m surrounded by in Northeast Missouri. Older white guys, and tractors. And cows, and tire fires, and Dollar General.

Picking tomatoes, apples, or cucumbers may be a simple joy for the home gardener. At scale however, this is work that cannot effectively become mechanized, unless human beings become the machine. Clearing long rows of commercial produce as fast as possible, under substandard conditions for low wages, well that’s less romantic than some white dude in a field of waving wheat, furrowing his brow in an epic stuggle of man and nature. Agricultural labor has always been exploited. It was the base purpose for slavery in the U.S., and once human beings could no longer be legally owned by other human beings, the powerful created new entrenched systems that were at as close a level of economic efficiency to slavery as they could get away with. These problems have continued to persist, from the exemption of farm workers from the National Labor Relations Act of 1936, through the history of exploitation of migrant labor throughout the 20th century, and on up to today where farmworkers are now struggling with increased heat during harvest work, and child labor is frequently employed everywhere from field harvesting to cleaning and sanitizing slaughter facilities overnight.

Sitting out near the hops vine, watching the golden, feathery cones sway in the hot breeze, thinking of all the beer being glugged out there this Labor Day, my mind turns to the Wheatland Hop riot. In 1913, the largest employer of agricultural labor in California was Ralph Durst, operating the 640 acre Durst Ranch outside of Wheatville, in Yuba County. Durst’s cash crop was hops for beer brewing, which would regularly be harvested by a crew of over 1,500 each August, before eventually being shipped to England, and brewed for that nation’s insatiable appetite for ale. But this year was different, and Durst broadly proclaimed in fliers and adverts that he was offering ample pay and unlimited positions to all who arrived for harvest by August 5th.

Over 2,800 men, women and children flocked to the ranch for work. Durst opted to hire them all, despite only needing about half of them, and consequently slashed the promised pay rates. Over-hyping available work and then driving up competition for low wages was a common practice in agriculture at the time. We seem to be doing this to ourselves nowadays in the YouTube age, but I digress. Conditions in the field and at the makeshift camp were abysmal. Durst charged the farm workers rent for a spot in the scorching hot tent city constructed on a denuded slope, could not provide sanitary toilets for the population, and did not provide drinking water within a mile of the field, but instead a for-profit lemonade stand operated by his cousin.

Then there were the wages. The expectation was that laborers would receive one dollar for every 100 pounds of hops harvested. Hops are light. The weight was totaled after cleaning, and the harvesters were not allowed to watch their yield being cleaned. Suspicion that Durst was purposely shorting the workers on their weights began to gain voice in the camp, and murmurs of a strike began to circulate. In addition to putting his thumb down on the ownership side of the scale, Durst also withheld 10% of each worker’s wages, promising only to pay the full amount at the end of the season to prevent laborers from walking off. In comparison to neighboring hop farms, workers at the Durst ranch we’re getting about half the wages they should have been.

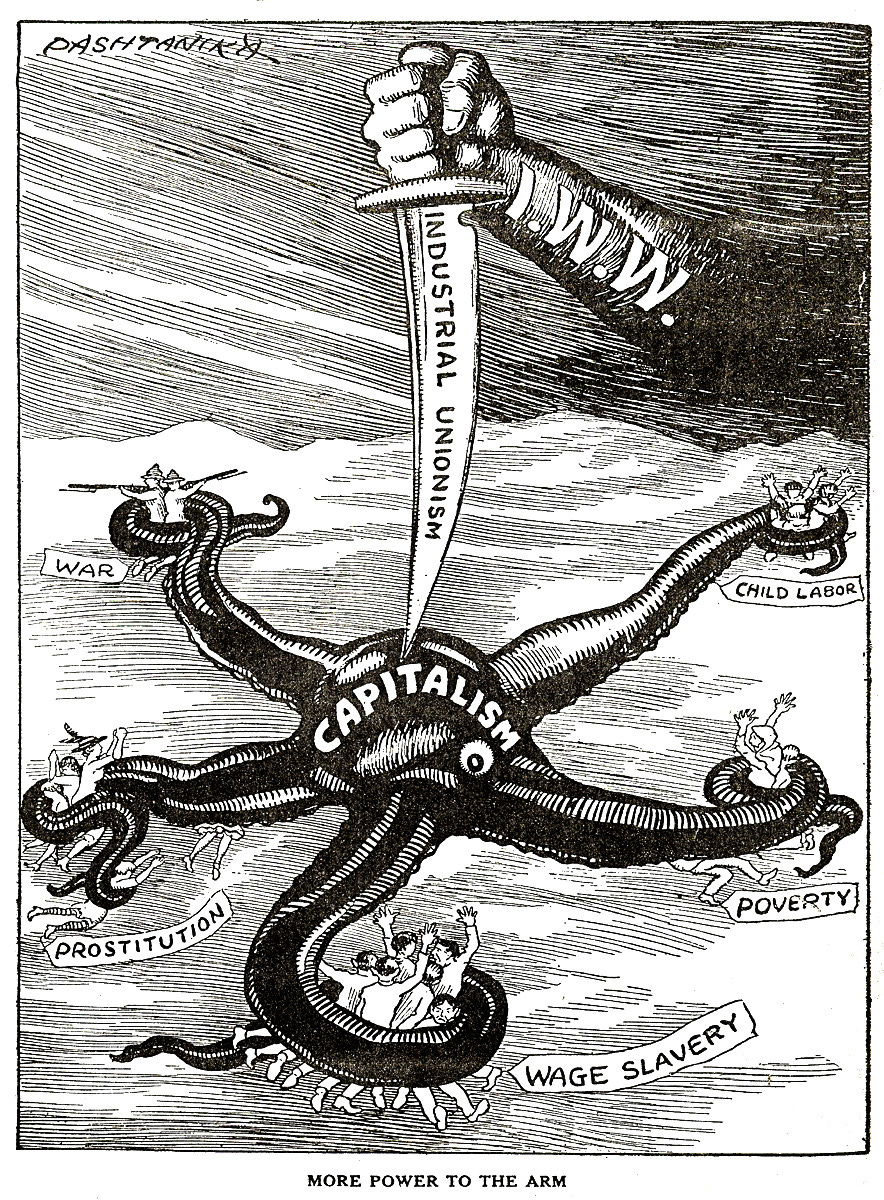

Enter the Wobblies. The International Workers of the World, or the Wobblies, were, and are, an international labor union, seeking to supplant capitalism with revolutionary industrial unionism. With ties to earlier anarchist and socialist movements, the Wobblies brought forth radical propositions such as the right of workers to elect their own managers, and agitated and organized in the manufacturing and farm labor industries, more recently moving into organizing labor forces within service industry corporations like Starbucks and Whole Foods. The IWW seeks a world where all workers are united as one single class. An admittedly lofty goal, but certainly one which many folks can relate to.

Among the 2,800 working folks at Durst Ranch were about 30 or so Wobblies, who elected Richard “Blackie” Ford as spokesman for the field workers, four days into the harvest, as living conditions continued to deteriorate. At the direction of the other workers, Ford began to create demands: $1.25 per 100 pounds of hops picked, worker access and control of the cleaning and weighing processes, drinking water in the fields, sanitary latrines, and paid work helping women and children lift heavy totes of hops onto the wagons. Durst offered to fix the toilet and water issues and allow one worker to observe the cleaning and weighing of the crop. The strike committee refused to accept these terms, and Durst promptly fired them from the ranch. But the wobblies did not collect their pay, and would not leave. A strike was imminent.

An assembly of organizers and hops pickers formed, singing labor songs and addressing the diverse crowd in English, Spanish, Greek, German, and Arabic, and when the proposition of a strike was put to a popular vote, the broad majority of workers raised their hands in favor. All the while, Durst was calling in local law enforcement and the district attorney to put the potential revolt down. On August 3, 1913, the Sheriff and his deputies approached Blackie Ford at the speaking platform. They were impeded by Ford’s fellow hop pickers, and in an effort to disperse the crowd, one of the deputies fired his shotgun. What happened next is unclear, and stories vary depending on which side tells it, but we know that a riot started, and that by the end, four men were shot dead: the district attorney, a sheriff’s deputy, and two hop pickers, one from England and one from Puerto Rico, who was alleged by some to have been the one to wrestle the shotgun away from the cops. A fifth man, a worker, lost his arm to a shotgun blast. The crowd of workers was not reported to be carrying firearms.

As the riot boiled over, laborers fled the ranch as the National Guard was called and local law enforcement swept in, making over a hundred arrests. Arrested field workers were subjected to starvation and beatings until they turned evidence on the organizers, though no evidence existed. One such worker was Alfred Nelson, who was held incommunicado at various locations, beaten with rifle butts and rubber hoses, starved, and threatened with execution. He did not fold or confess to any crime and eventually, the Swedish consulate in San Francisco lodged a formal protest of the actions against Nelson, who was a Swedish national, until he was released.

Arrest warrants were issued for Blackie Ford and fellow organizer Herman Suhr, for murder. No evidence or testimony implied that these men were ever seen holding a gun, except for an alleged verbal confession by Suhr, which Suhr vehemently denied. A trial was set, and the judge, E.P. McDaniel had been a friend of the murdered district attorney, who also happened to be Durst’s personal attorney. Despite this, a change of judge or venue was denied by the governor, and after a quick trial and one day of jury deliberation, Ford and Suhr were given life sentences for second-degree murder. Blackie Ford was paroled a decade later, only to be re-arrested and tried for the murder of the sheriff’s deputy. After 77 hours of jury deliberation, he was acquitted. Herman Suhr received a pardon shortly thereafter.

So if you’re cracking open another Labor Day beer about now, why not raise a toast to Herman and Blackie and the other 2,800 hops pickers at Durst ranch on that hot August back in 1913?

The organizing activities of the Wobblies in the early 20th century merely scratch the surface of farm labor struggles in the U.S. Other groups, like the United Farm Workers (led by Dolores Huerta and Cesar Chavez and organizers of the Delano grape strike), the National Farmer’s Union, and the Farmer Labor Party have worked to improve economic and labor conditions for farm workers and even small-scale owners and operators looking for an even field to compete on in the “free market”. In fact, the rising populist movements associated with agriculture and labor in the early 20th century caused wealthy industrialists to respond by forming their own political entity at around the same time: The National Farm Bureau. To this day, and in this very county, the Farm Bureau is alive and quite well, working to see that the activities of our largest ag corporations like ADM, Cargill, ConAgra, and DuPont can be performed, unchecked by authorities from the county and municipal level on up to the federal government. And they appear to be winning. But that’s another story for another day.

Back here at this farm, I have stopped my writing on and off to get dinner, close up the turkey wagon, help to gather scionwood for pear grafts, prepare the kids for school, and check on all the tomatoes in process. I’m working well above an eight hour day, every day, and I fear that the conditions under which I work are wearing and breaking my body. Adjusted for inflation, I’m not sure that I’m making as much as the Durst ranch hop pickers, but I do have water. The toilet situation, well, it’s probably better, not sure by how much. I am both the exploited worker, and the oppressive boss here, and if I go on strike, everything I care about will die.

It wouldn’t be fair of me, to compare my own plight with those of the migrant kids they’ve got cleaning the slaughterhouse kill floors, or the heat-stricken field workers toiling in the Central Valley sun to bring abundant, year-round produce to all corners of the country. No, I’m maybe a step closer to that rugged, mythic farmer depicted in commercials and other media, my exploitation self-inflicted, my struggle inextricably tied to place, climate, and the unseen forces of the economy.

All those thriving homesteads on social media, scenes of abundance, simplicity, connection that hearken back to a false history of self-determination and independence… they aren’t real. And perhaps they never were. Reflecting on a decade spent doing the hard labor of farming, I’ve come to understand that projects like this are unlikely to succeed at creating a substantial change in the food system. In lieu of a Ralph Durst, I have become my own oppressor on this piece of dirt, and if conditions do not improve, my broken body will not long wait to be beneath it.

The hot wind has stilled and left the air beneath this old hedge tree dank and thick and ridden with evening mosquitoes. I’ve never harvested more than a few hops from these vines… but right now, they are ready, golden, resinous, intoxicating, and perfect. At some point in my homesteading career, I decided that home-brewed beer and home-grown potatoes weren’t worth the hassle. Potatoes are cheap, so cheap that even I would rather buy them than invest the labor in producing them, at least while such things are still available on every store’s shelf. As for beer, I try not to go near the stuff these days; too many reasons to not quit after a single can, but likewise, beer can be easily obtained with currency, more easily than with toil. But I do admit some strange attraction to picking a passel full of these wild hops this year. Perhaps it would be in honor of Blackie Ford, Herman Suhr, Alfred Nelson, and all those Wobblies and hop pickers back a hundred and ten odd years ago. Or an exercise in toil, or self defeat. A bitter harvest, to celebrate the labor from which I cannot be liberated. Not this Labor Day, at least.

In solidarity,

BB