Kickin' Hickory

Tick season, barochorous dissemination, and a big-budded tree that's surprisingly overlooked

In the morning after a moderate spring rain, the wet earth is speckled with faded plum petals, spent cottonwood catkins, and clusters of elm seed– more elm seed than I’ve noticed before. Our pigs, finally let out to graze in the vernal green-up, lay snoring in the thin shade of barely unfurling oak and locust, spattered with with papery, faded elm samaras, their dewy bristles festooned with germplasm and other tissue and detritus related to tree reproduction. Once they hear me coming with their morning pail of whey, they’ll shake and grunt as they rise from their thatchy nest, trapped steam rising in the morning cool, shaking the elm seed off their bodies and stomping it into the moist sod of the pasture.

Rains this time of year always seem to bring out a healthy and active population of ticks, and I almost imagine the detrital showers of spring to be their sprouting point. In some areas, it seems that nearly each blade of grass is tipped with a questing tick. As with the elm seed, I do not recall as abundant a tick season as this one. I come home from chores, field work, dog walks, and birding excursions crawling with them, my body speckled with little scabs and bites. I’ve begun making it a point to check those parts of myself I can easily see a few times daily, pulling off parasites of all sizes and drowning them in rubbing alcohol– the forbidden spring tonic. Then, before bed, I get some assistance in one of the least romantic acts a couple of people can perform without clothes. Sometimes, I feel their ghosts on my skin while I lay in bed.

So long as I do not contract some tick-borne illness, this is a small price to pay for engaging with land here in the springtime. Nightly, warblers migrate into our airspace, alighting on damp branches in the fading dark– Tennessee’s, yellow rumps, all the flashy little passing tourists I almost forgot about. A person could go hunting morels, but I prefer to look up. Most importantly, I choose to tolerate ticks so that I can plant more trees, here at the confluence of warm earth and approaching rain.

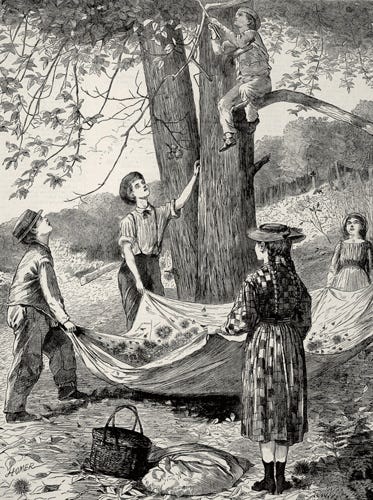

Early last autumn, while stomping in the wet sand along a shallow meander of the Middle Fabius River in search of cliff swallows, I witnessed a small yet reassuring natural occurrence– hickory nuts, still in their hulls like little green pumpkins, floating and bobbing along in the riffles of the creek. Looking up at the nearby embankments, laced through with muddy poison ivy leaves, crack willow, and slumping boxelder boughs, I could not find any hickory trees present in the canopy. As the little pumpkins spun through the foamy surf of the lazy stream, each one bearing a hard-shelled nut, I loped alongside to watch them. Some bounced off sticks and rocks and sandy shoulders, rolling into the alluvial mud of the bank, where if they escaped the jaws of squirrels they might still lie, just now beginning to push their radicles down into the dirt. Others continued on their jaunt, perhaps to arrive ashore further downstream in such noted hamlets as Ewing or Maywood, or perhaps even all the way to the mouth of the Mississippi River and on over into Illinois. A small observation, but one that has stuck with me throughout the dormancy of winter. I decided to plant hickories.

Unlike some of the neighboring properties, the land here supports very little hickory, for some reason. When I see this notable of a drop in tree species populations across ownership boundaries, it almost certainly suggests that the hickories were specifically logged out, and completely enough to thwart regeneration. My best estimation is that this occurred sometime in the last 50-70 years. While hickory has always been valued for its durable hardwood– choice stock for tool handles, baseball bats, and wagon hubs, it is very hard for me to imagine that it all went to this. Hickory wood burns hot and consistent, and some of it could have been used for the brick kilns that once dotted Northeast Missouri. Some of the choice logs could have gone to flooring and fine timber, and the fact that this was once a fair-sized, traditional hog operation before the 1980’s farm crisis–before pigs were more often moved indoors to expensive facilities at the behest of feudal ag conglomerates and their serf operators– means that free-roaming swine may well have reduced the hickory seedbank as more and more open fields were put into row crop. This is all just informed speculation, but I’m certain that the reason we have few hickories here is rooted somehow in the staccato cascade of human disturbance and resource extraction prevalent in the midwest, where the topography and soils are easily subdued by machinery.

There is but one pocket of young hickories here I know of, a sparse, weedy thicket in the intermittent floodplain of the Long Branch creek, where out and among the Reed’s canary grass and razor-whip tangles of multiflora rose, an assortment of young shagbarks and bitternuts rise from the sodden alluvium, likely planted by rising water. They struggle in the weeds, their scarred trunks thick and shortened by deer browse. In the last few years, we’ve begun building deer and stock-proof shelters for them so they might have a chance. With the heavy duty welded-wire cages in place, we can safely graze cattle, goats, and swine in this area in order to reduce grass and weed competition, and also to rob attractive browse from the deer. Preliminary results of this effort are inconclusive, but we’ve picked up a lot of ticks in the process.

Thinking about those floating hickory nuts, and seeing the small, gradual signs of hickory returning to the land here down where the creek floods, got me to thinking about planting more hickories, particularly on some steep slope somewhere that the seeds would be sure to roll downhill and travel the meandering waterways until they found their way to where they were needed. At this current rate of resource extraction, stewarding and maintaining some collection of hickories here has the potential to support threatened ecology as well as human communities. Shagbark hickory in particular is known for providing summertime shelter to the endangered Indiana bat (Myotis sodalis), an animal that should be present across our watershed but continues to rapidly decline due to White Nose disease, pesticide use, habitat loss, agricultural practices and wind turbine power generation. Squirrels, deer, and rodents of all types relish the hard-shelled nuts, and the tree’s foliage and bark itself is a critical food for over 200 insects.

The genus Carya contains 19 accepted species globally, and a good amount of them are present in temperate North America. Our earliest known fossil records of hickory pollen arise in Mexico and New Mexico, and modern Carya fossils appear in Oligocene strata from 34 million years ago. It has long been a critical member of the Eastern North American landscape. Fossil records also document how the shells of hickory grew thicker and stronger over time in response to rodent pressure. There is a general rule of thumb with hickories that the thinner-shelled nuts are more bitter and tannic, whereas the thick-shelled species contain sweeter seeds, with the exception of the Sand Hickory and the only Carya species to break into large-scale commodity production– Carya Illinoisensis, or the pecan.

Now, I’m not going to argue that pecans aren’t pretty damn good, because they most certainly are. They are thinly shelled, buttery in flavor, heavy and consistent in production, and we have a lot of commercial infrastructure in the US that can handle them. Of course, there are downsides too. The thinner, lighter shells are prone to varmintry, and as with any scaled, cultivated crop, pecans co-exist with an expanding population and variety of pests and diseases which complicate community-scaled production. As with any commodity, scales of economy prevent folks growing only a handful of trees to benefit financially.

Contrast this with what I would argue are the two best-eating hickory nuts– shagbark and shellbark. These shells are incredibly tough, and the nutmeat of shagbarks in particular has a tendency to shatter upon opening, which does not easily lend them to industrial production. The nuts themselves are delicious: they taste both fruity and earthy but are broadly agreeable, unlike black walnuts which I would say bear a controversial, almost cheesy/floral flavor palate. The thick shells of these nuts help them to keep in storage for a much longer time than pecans without going rancid, and the crows and jays and squirrels have to work much harder to take off with them.

An issue with wild hickories, and one which further cultivation and breeding could address, is inconsistent masting. Masting trees, such as hickories, oaks, and beech, display a phenological strategy of dissemination. In some years, the trees in a particular region may mast heavily– an oak may produce thousands of acorns, but in most others, a much smaller amount. We have some good guesses as to why. The predator satiation hypothesis suggests that inconsistent pulses in seed production evolved in some species which coexist with heavy predation (squirrels, deer, jays for example) so that a baseline predator population would be overwhelmed by the abundance of seed every so often, and therefore, not every seed can be eaten. In other words, if all the oaks in the forest were to produce consistently large amounts of seed every year, this would support a larger population of deer. It wouldn’t matter how much seed the trees produce annually, it would all mostly be consumed, because the population and survival rate of acorn-eating critters would remain synchronized with the expected yield.

Another hypothesis on the nature of mast seeding is resource matching. It takes nutrients to produce seed– nitrogen, carbon, water, and phosphorous, to name a few. These nutrients are noticeably depleted from soils after a mast year, and it may take a few years for the necessary energy and nutrition to regenerate in soils to reproduce heavily. The metabolic cost of seed production is so notable that tree ring histories often display slighter growth in mast years, similar to fire and drought– a tree that is stressed by heat will often have a corresponding drop in mast. And of course, weather is likely a proximate driver in reproduction. Late frosts and heavy rain at flowering can have damaging effects on pollination, and reduce seed production.

Prior to colonization, forced displacement and slaughter (and the subsequent industrialization of food) hickory nuts were a vital foodstuff for indigenous Americans. Fresh nuts, milks, and oils were all perennial staples in the diets of Eastern Woodland culture since the middle-Archaic period, and even here in “modern” Northeast Missouri, the old timers sometimes recollect harvest, smashing, and eating the nuts as a seasonal treat. In fact the origin of the word “hickory” come from the Algonquin “pawcohiccora”, used to describe a common hickory-nut stew. Thin-shelled pecans were obviously a much sought after and important component of all this, but their natural range is limited in comparison with shagbarks, shellbarks and others.

This is all to say that while pecans are tasty and well-adapted to scaled commercial production, their other Carya cousins hold many benefits for both ecology and human culture. It is often taken for granted that perennial crops are more resilient than annual crops, and while I largely agree with this logic, the caveat may be that a deeper resilience comes from having a complete diversity of adjacent tree crops. At a time when pecans orchards are threatened by fungal diseases, various scabs, blights, and —most significantly– a changing climate, other Carya species might provide a more stable alternative.

Earlier in the week, some friends and I made progress on our newest tree planting– a project that I’ve been calling Operation: Indiana Bat (privately, in my own head, to avoid embarrassment). The goal was simple– find an appropriate plot of land to introduce hickories and a few other native food-bearing trees, plant them, care for them, and wait for the nuts to start rolling, probably around the time I’m in my sixties. I might fall and break a bone out there fiddling around at that age, but not before kicking a few shagbark fruits down into the Long Branch to drift downstream. The Missouri Department of Conservation has long provided cheap, well-produced stock of mixed hickory seedlings, but I wanted to increase our odds of planting, propagating and distributing germplasm with a high degree of human food value, and this is where we are standing on the shoulders of giants, or at least weirdos.

Archaeological evidence of hickory cultivation such as the Victor Mills site in Georgia, and the existence of disjunct populations of thin-shelled sand hickories outside their typical range in Delaware and Southern Indiana suggests that indigenous Americans planted, tended, and relied on hickory nuts as a perennial staple. The colonizer John Smith refers to being served hickory milk by the Powhatan people already living in Virginia. It would seem to follow that like other indigenous crops, many of the hickories (and not merely the pecan) would be co-opted and cultivated by European colonists, however most references to hickory crops during the early colonial time period dismiss it as a pannage crop for swine, earning the common name for Pignut hickory for species Carya glabra, though here in Missouri, folks often erroneously refer to black hickory (Carya texana) by that name as well. And while many old timers around here can remember smashing the shells between bricks and picking out shagbark meat as little farm kids, intensive hickory cultivation never took off at scale after colonization, with the exception of a handful of nut enthusiasts and visionaries.

John Hershey was one for sure, though I don’t believe I can do his story as much justice as Andy of the Poor Prole’s Almanac did in this profile here. More obscure, but equally consequential in the modern cultivation of Carya is Fayette Etter. I cannot find an incredible amount of information on the man, but we know he was a telephone lineman working in south-central Pennsylvania. In his spare time, or perhaps on the job when he was working in the timber alongside his service route, he sought out the best wild hickories, propagated them, and even experimented with cross-breeding. Sometime in the 1950’s or 60’s, Etter showed up at the courthouse in Franklin County to fight against a bridge improvement project that would eliminate a particularly notable shagbark, one he had dubbed “Keystone”. The story is told that Etter confronted the judge with a large specimen nut to crack and eat. The judge took a sample, declared it to be “the finest nut I’ve ever eaten”, and the bridge was relocated two miles downstream. The following year, a flood on the river destroyed the new bridge and the “Keystone” hickory, but Etter had managed to propagate it from scionwood.

This year, our agroforestry cooperative was able to obtain seedlings from selections by John Hershey and Fayette Etter via Future Forest Plants, and while I’m shouting out nurseries, my buddy’s nursery, Perennial Crops, also carries a wide range of selected and improved Carya seedlings which we received to help kick off Operation: Indian Bat last fall. And so, the seed rolls on, slowly as it may. Tree seed improvement is work that takes place over a chain of many lifetimes, and conventional agriculture has little time or attention for it in our age of instant gratification, not to mention instant profit. So I suppose it will be future nut enthusiasts who will keep this work moving along.

Of course, for hickories to take off as staple foods, harvesting, processing, aggregation and distribution will all need some attention as well. Cooperatives like Keystone Tree Crops are doing interesting work with hickory oil production, among other things. They are working with Carya cordiformis, which has the unfortunate common name Bitternut hickory (there’s an interest among connoisseurs in changing the parlance to “Yellowbud” or “Oilseed” hickory). While tannin rich and therefore bitter, this tree has the potential to produce a considerable yield of cooking oil, rivaling olives in terms of land use. The oil pressing process leaves behind the tannins, and the leftover cake might find further use in livestock feed or organic fertilizer products. For Carya to reach it’s full human-use potential beyond timber, we will need not only the work of farmers and breeders, but inventors, food scientists, mechanics and engineers— and most of them have to be a little nuts.

Covered in ticks, I take a walking tour of the budding trees– pin oaks unfurl their leaves, soft as a mouse-ear, their pendulous catkins glittering with pollen. Little spears of stretching leaftips poke out along the spiny, weathered boughs of Osage orange, and the waxy fans of young poplars dance frantically in the slight wind. Nearly every tree has broken dormancy in earnest, but the hickories are particularly slow to start. Their buds are enormous and elongated– big ol’ buds. Some have begun to slightly split open, and soon enough, splashes of wide-tipped leaflets will explode throughout the rich bottomlands and wooded hill-tops here in Northeast Missouri. And here, in our little corner, there’ll be just a few beginning that long slow cycle of growth, repair, and regeneration. I’ll kick a few downriver for you in a couple decades.

Great piece! Thanks for throwing some links to nurseries. I’m planning on planting some hickories in my growing orchard. Where do you acquire your tree tubes from?

loved reading this—learned a ton and it was easy, conversational reading. and i can relate to the ongoing tick detection battle. thanks for your writing & your tending of the land