Pin Oak

or The Last Pioneer in the Age of Total Extraction

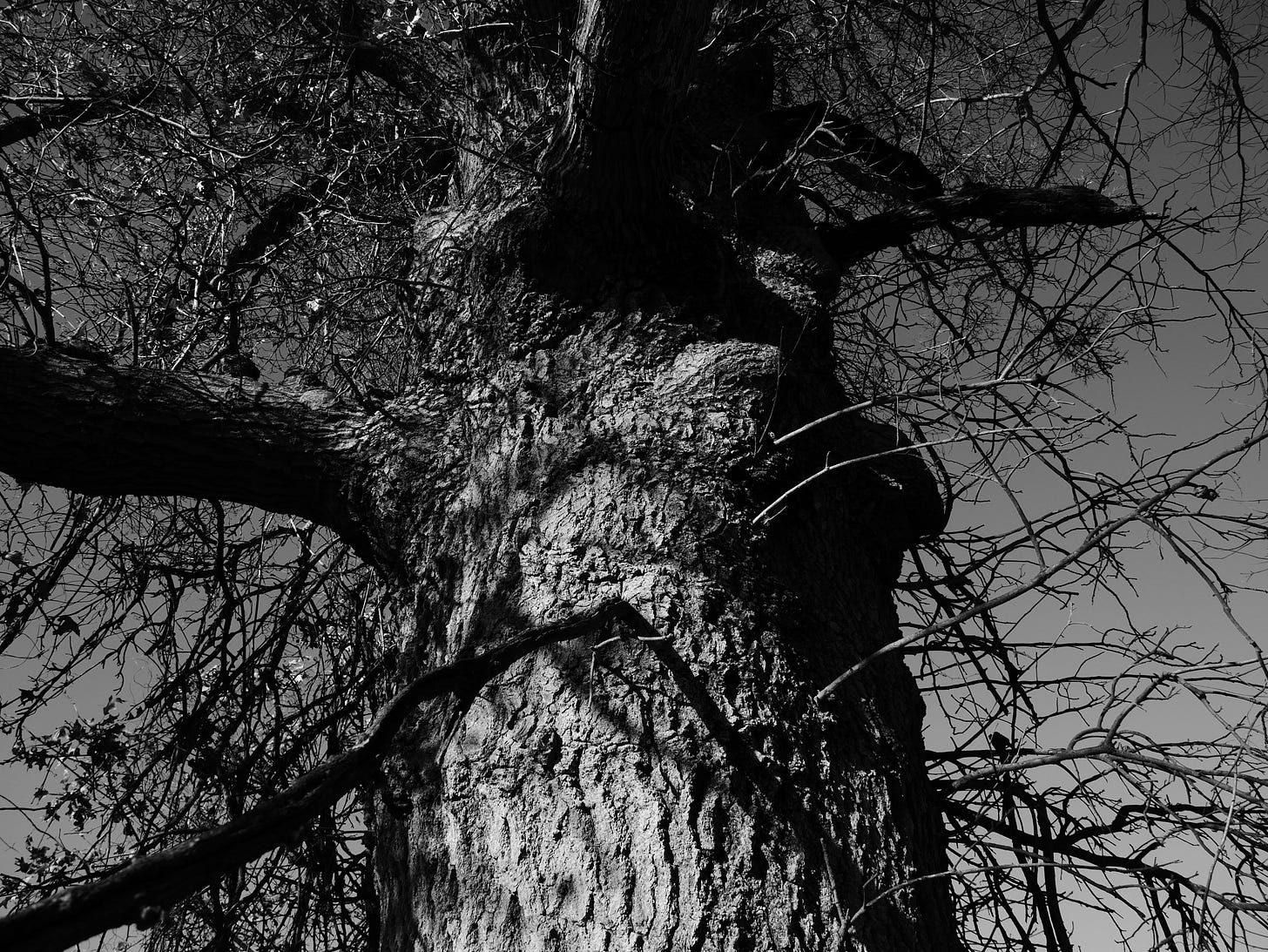

In the thawing draws, where tired and dying American elm rots to the core, I am raking seeds into the mud and duff ‘neath pin oaks. They are everywhere here, standing like caltrops, like great, vertical wooly bear caterpillars, marcescent, projecting their tough side branches like a living barricade along the tender, eroded scar of this slope, balanced deep in the clay on deep-reaching roots. Pin oaks, like eastern red cedar, are defenders of our vulnerable soil here in Northeast Missouri. They are also, like eastern red cedar, a pain-in-the-ass tree, which I find endearing, at least here from the writer’s chair.

The pin oak (Quercus palustris) is so named because its trunk is studded with low-hanging, almost-contorted branches, or pins, which some accounts suggest were actually used for wooden pins for carpentry and timber-framing in earlier times. The thick, flexible “pin” branches, in addition to making pin oak sawlogs not worth the effort, are also extremely dense to move through. As a person who has been stumbling through pin oak for going on 15 years, I can assure you that these branches are both very tough and very springy– several times I have pressed them out of the way, only to watch the swinging limb swat back at whoever may be following me. I have also been victim to this action, both on account of friends (because friends don’t let friends fell trees in the woods alone!) and goats alike. Mostly goats.

These inconvenient limbs can form a barrier that slows or dissuades human/large animal intrusion into sensitive, healing areas, as pin oak is a relatively short-lived “pioneer” oak, arriving early on the scene to scab over the ruts and scars of anthropogenic disturbance and extraction. While pin oak is less intimidating than say thorny Osage orange or honey locust, I have been discouraged from cutting across draws and gullies hundreds of times by young, dense groves of pin oak and their tangled walls of intertwined branches that snarl across regenerating woodlands.

Pin oaks, particularly when young, present a trait known as marcescence, that is, they maintain their leaves throughout winter, not like an evergreen, but as an orange, desiccated canopy of spent photosynthetic surface, remaining on the tree until next spring’s bud break. These stubborn leaves act as a vital umbrella for winter rain and snow, protecting the fragile soil below from excessive precipitation that can lead to dormant-season flooding, while also providing excellent shelter for wildlife. In yesterday’s drizzle, my pigs spent more time out under the embrace of marcescent pin oak boughs than in their portable shelter, preferring the cozy layer of soft duff accumulated at the base.

Raking seed into depleted pig pasture near a rising stand of black locust, a mix of native warm-season grasses and palatable, pollinator supporting forbs, my rake catches the edge of a squirrel cache of a few dozen small, pin-oak acorns. Squirrel drays lilt and wave in the canopy, nests of twigs and oakleaf lined with empty shells and fine, nibbled bark. In September and October, as jays and crows swept in for the season, I would watch them hop and glide from pin oak to pin oak, plucking the small, bitter nuts on their raids, accidentally dropping a few here and there for the wild mice or to resprout.

While particularly unappealing to most humans, the pin oak acorn is a prized food for turkey, deer, and even wood ducks. In mast years, pin oaks can produce heavily, ready to resprout in the flooded-out tails of rootless gullies, the forgotten seeds caches of pouncing squirrels, and the decaying crops of ducks and jays and turkeys and crows dead and reabsorbed into the thin-soil clay. The seed is small, light, and round– perfectly suited to be carried point-to-point, or rolled down hillsides towards sodden bottomlands and deepening wounds in the earth, each sprout a stitch, weaving together broken networks of bacteria, fungi, microfauna and mineral dirt.

Pioneer plants, that arrive after disturbance and upheaval on the landscape, are different from pioneer people. I do not know of any examples where pioneer plants create the disturbance that they later exploit, but pioneer people have. When smallpox was introduced to North America, it advanced through the Indigenous population well ahead of the actual geographic settlement of the continent’s interior. By the time pioneer people made their way to Northeast Missouri, most of the original inhabitants may have already been killed by the disease, their legacy of fire-management and stewardship already fading as the wooded bottomlands gradually expanded from the boundaries, thousands of acres slowly creeping into a tangle of pin oak and thriving elm.

Good sawlogs of hickory, walnut and white oak were taken, and then came the plow, penetrating the strata of 10,000 years of prairie grass cycling from growth to dormancy to decay and back. The hills and plains were gutted for their rich earth, left to bleed mud in the creek-beds, channelized and without beaver. But the pin oaks that lingered at the edge of creek-side dales, sprouted from squirrel cache and bird’s beak would remain– too hard to saw and likely to bow for high-value lumber, too difficult to access for all but the most desperate homesteaders seeking fuel for woodheat. Seed by seed, pin oak has regained ground against the now fading settlements of those pioneer people. With every season, as our town squares crumble and main streets lay quiet under falling brick-piles in Northeast Missouri, pin oak creeps further up the slopes, stitch by stitch, the final seed sown after extraction fades into depopulation.

Pioneers, both botanical and anthropological, tend to grow fast and die young. Oaks, generally, are renowned for their longevity, but the pin oak seldom lives longer than 120 years. There are a handful of great big pin oaks here, doubtlessly matriarchs to the thickening groves that spring up along the sagging fences and cow-stamped draws quilting this township together. They themselves were progeny of an elder generation, cast down in those times when the sod was killed furrow by furrow, plot by plot. Due to those wide, low, spreading branch-walls, a grove of pin oaks is less hospitable to troublesome generalist invasives like bush honeysuckle or multiflora rose. Pin oak was here well before we arrived, anticipating the wounds we would create, and will be here long after our communities have been entirely bled from the land by the economics of tech-pioneers and autonomous, machine-operated extraction.

Despite its reputation as a pain-in-the-ass tree, alive or dead, I have managed to survive largely on pin oak for many years. I have raised generations of turkeys, swine and ducks on the seed, heated my home, built with it (despite its reputation), harvested the logs for propagating mushrooms, used it as shelter for my stock, and pruned backwoods pathways beneath its canopy for both recreation and tactical concealment. I won’t be here forever, but pin oak will, repairing what I could not regenerate, soothing the wounds that I myself am culpable for.

I cannot side-step the fact that our world has gone mad here by just writing about some of my favorite trees. The efficiency with which resources can be extracted, the complete ability to bulldoze entire ecotones for valued minerals and oil shale, is something that even persistent pioneer plants like pin oak cannot compete with. Unlike those old pioneer people, who at least needed to physically engage with the resources they took, the work today is done with drones, aircraft carriers, late night phone calls, a few electronic transfers, a God knows what else.

I think about the big old witness trees, those haggard matriarchs lined with thick vines of poison ivy and razored briar whips, who stood as young saplings at the end of the furrow and watched successive waves of progress and regress, injury and repair, and wonder who will do the work when they’re gone. Who will stand long enough to tell the next story? Will it be humans? Obviously, the greater balance of power in this world must be restored, but in the meantime, we need repair. Who will provide it, if not the pin oaks? The work of extraction is done from a clean distance— the work of the woods remains dirty and intimate.

I’m a pretty amateur forester. I like looking at trees, walking among them, and even measuring them, but if given the choice, I never really like to cut them down. That’s not for sentimental reasons either; it’s hard dangerous work and I’m accident-prone and increasingly lazy. Still, we have a bit too much pin oak here. Pin oak holds its ground against other trees pretty resolutely. Without selective cutting or some form of natural disturbance, those original trees that were cut for their economic value –the white oak, the hickory, the walnut— won’t regenerate in the woodlands. Pests and disease have done much to reduce the population of elm and ash, and so in order to reintroduce some diversity into our damaged woodlands, a few oaks need to go every year.

We create openings and experiment with restoring other tree species. At times, we graze or pasture our animals among the pin oaks, carefully; pruning and seeding and creating new opportunities for forest diversity to express itself. But whenever I find a nice stash of pin oak acorns, I tuck a few in my pocket— you never know when you’ll find some place that needs them.

The Fox Holler Almanac is a reader-supported publication— I couldn’t do it without you! Share or leave a comment if you liked it. Hell, leave a comment if you didn’t, though I might ignore it. And if you feel moved and able to materially support my work, upgrade your subscription or buy me a coffee.

Thanks, y’all.

I once read that Marcescence is an ancient defense against megafauna. I agree that they are a pain in the ass. In the 70s towns planted them everywhere. I stopped planting them when I cound not mow under them without getting beat up. Their lower branches move straight down. I have them pruned up almost 12 feet and they still go low enough to make mowing w a rider dangerous for face and eyes.

Beautiful meditation. That line about extraction happening from a clean distance while repair stays dirty and intimate really captures somthing crucial. It's the same dynamic we see in tech circles where people build algorithms that affect millions but never have to witness the downstream mess. Meanwhle the actual work of fixing broken systems falls to those closest to the damage.