Pruning and Other Forms of Tree Sorcery

The ordinary magic of manipulating time and space in the orchard

I’ve been looking up lately. Between my renewed interest in birdwatching and the necessities of orchard pruning season, the tendons and muscles in my neck, not to mention my shoulders and wrists, have been used in some unfamiliar ways this past week. In these late hours of pre-emergent dormancy, my creaking body, stiff with the corrosion of wintertime sloth, quite clearly needs the yogic realignment proffered out at the ends of pear limbs and tops of orchard ladders. Pruning season beckons.

I do not know if pruning, particularly fruit tree pruning, comes naturally to anybody. It is a complex act, a manipulation of biology, energy, space and time– each snip, clip or stroke of the saw informed by decisions made (or left unmade) in the past, with the potential to significantly affect future outcomes in the life of a tree and the community that surrounds it. Standing on the ground and looking up, the novice tree pruner can, understandably, feel intimidated. And with young saplings, clipping luxuriant growth down to a three foot stick can feel like a cruel and wasteful act. In the rehabilitation of older trees, the dropping of a limb, with dozens of potential fruits, can give rise to a mournful sensation in the caretaker.

There’s a lot of rules to pruning, and I’m not sure what the first one would be. Perhaps it is to sterilize your tools and keep them sharp. And, circumstantially, there are exceptions to many of the guidelines I go by. A piece of advice I’ll offer is that you kinda need to just do it. Make a few mistakes even. With a pair of sharpened pruners, or even loppers, there isn’t too much damage a person can do in a season of pruning that can’t be undone in a season of growth. The exception to this advice is if you decide to make the same mistakes several seasons in a row, or worse, the responsibility for maintenance of the tree passes from novice to novice without anyone ever developing a circular relationship with tree.

Over time, the action and response of the studious and observant orchardist will give way to confidence. Instead of standing nervously and befuddled on the ground looking up, the advanced tree pruner becomes similar to other denizens of the arboreal world– skittering across limbs like a squirrel, clinging against the heft of the trunk like a nuthatch, deftly moving the beak-like appendage of their gleaming tools through the twigs and shoots in order to redirect the flow of energy towards fruiting, and the long term health of the organism. But the orchardist, at their full power, is no longer a mere denizen of the limbs and leaves– they can become something more akin to a sorcerer, concerned with manipulating the temporal, spacial, hormonal and energetic flow of the tree and its environs.

Tree wizardry, at its most basic, requires a zoomed-out perspective on time and growth. Prior experience, both easeful and difficult, in harvesting from mature trees helps. Harvesting standard apples and pears is sometimes best performed while climbing. A well scaffolded tree with sturdily jointed limbs can support the careful assent of the nimble harvester, whereas the cumbersome and often precarious dance of orchardist and orchard ladder can be dangerous as well as tiring. The clairvoyant pruning approach is to transcend time and imagine how each limb can be placed in a spiraling rung in future years for the benefit of the fruit gatherer.

The supernatural orchardist, at the peak of their power, needn’t rely on much technical esoterica. Here in the organic tree crop world, there is an unceasing product line of expensive potions available to (allegedly) feed microbes, make soil nutrients more bioavailable, enrich the energy absorbed by leaves and transported to root exudates by way of the phloem, or encourage more abundant fruiting. Alongside all the magic sprays and root drenches, there’s also an increasing torrent of new techniques and information, presented all over the internet. While I’ll admit to importing some amendments at the initial tree establishment myself, I am increasingly developing potions of my own, that save for a little mineral oil or slaked lime, needn’t require me to leave home to acquire.

Like most of us, a tree looks out for its own best interest, and naturally extends this to the microbial world. A native tree, rooted where it naturally belongs, builds relationships with the dirt. What that tree drops– leaves, fruit, twigs– are host to the composition of soil life that supports the continued existence of that particular tree, and its progeny. To extend this thinking, albeit presumptively, the fruit tree also drops, produces, and exudes the necessary building blocks of beneficial soil life. But an orchard tree is not a forest tree. It is a wounded thing, planted out of context of its evolutionary home and isolated from its ecosystem of origin. In Northeast Missouri, a pear or peach tree is far more vulnerable than a maple or oak. And while all the necessary composition of nutrients needed to build the proper soil life communities may well be present in the dropped fruit and detritus, these leavings also harbor pathogens, harmful fungi, or damaging pests.

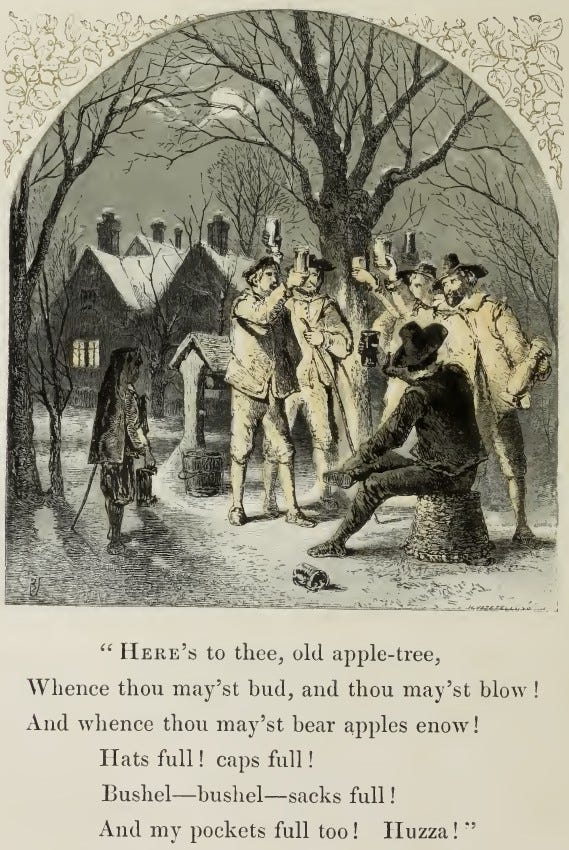

So the supernatural orchardist delves into alchemy– fermenting fruit drops, extracting vinegars, swirling dilutions of the stuff in rainwater and forest duff and atomizing it by the full moon. It might not really help, but its certainly safer and less energy intensive than many imported products, and like they say, it is the shadow of the orchardist that is the best fertilizer. It’s noteworthy that feeding fermented fruit back to the tree from which it was borne is nothing new– in fact this is the central concept of the Apple Wassail, a mid-January (Twelfe Night) tradition in the cider orchards of Southern England, in which bread or toast is placed around the tree and drenched with the last bit of cider in an appeal to the orchard’s resident spirits for another bountiful crop.

Apple Wassail- also known as drunkenly accosting a tree when it’s bone cold out.

Then there’s the baumbock. You may recall earlier discussion of the feldgeister, the field spirits or “corn demons” of agrarian German folklore. In brief, there’s a lot of ghostly wolves, demonic bears, witches with bosoms filled with molten iron, and supernatural chickens out on the farm, and if they’re not fed appropriately by leaving some of the crop unharvested, the fields lose fertility, or maybe your children get stolen or eaten. Classic stuff. Well the baumbock, or tree-buck is one such feldgeister, taking the form of a randy billy-goat who will fertilize your fruit trees over winter if properly fed. On our farm, the relationship between goats and trees is a bit more fraught, but our goats are fully corporeal. Nonetheless, folkloric practices like leaving food in the field to engage wildlife, or subtly adjusting the soil life with fermented fruit and bread as a growth medium may have some slight influence on soil and ecosystem health, and thus, fruit production.

Regenerative agriculture, and by extension, regenerative orcharding, is at best, a young science, even though the ability to grow food while sustaining soil has been present in many cultures for time immemorial. It’s almost like the problem with extractive agricultural systems has less to do with the lack of foliar sprays, microbial inoculants and assorted magic potions and more to do with the presence of capitalism, but maybe that’s just me. These types of purchased products are a natural reaction to wanting to solve a big problem with a young, limited understanding of its depth. Soil science is so complex, so variable, and so nuanced that we may as well use magic. I just wish these companies hocking potions, certified organic or otherwise, would come clean about whether their wares are designed with research or sorcery.

Me, I largely gave up concocting potions in childhood, but perhaps I am not fully aware of my powers. I can, however, use my senses. At ladder top, I use my bare skin to note the subtle flow of air on near-still days, and angle my saw with precise care to allow for a purifying breeze. Other folks rely on the idiom that the branches should be spread wide enough to allow for a basketball, or sometimes a cat, to be easily passed through. My cat is much different in size than a basketball, so I just feel the breeze instead.

You’ve got to be careful for the fruiting spurs up there. Watch your elbows! Leave the center open and the branches pointing out. Remove no more than a third of the branch mass per year, and prioritize cutting out dead, diseased and crossing limbs– following these baseline rules will help develop your confidence. And always disinfect your tools, between trees if not between limbs. We carry around an alcohol soaked cloth in a plastic bag for quick wiping. I can tell you these things, or you can study diagrams. I’ve been very fortunate to work in close proximity with mentors, some of which may even have supernatural powers. But words of advice and two-dimensional charts sometimes fail when you’re in the tree’s hulking embrace. And that’s where the magic comes in.

Working strange spells out in the field.

Magic, I suppose, is predicated on faith. I’ll admit, I’m not really stocked up on either faith nor magic. But I’ll also admit that a little bit of woo woo, in the face of such an absurd task as feeding the world without doing much harm, goes a long way towards getting my ass up a ladder. At least when I’m down here, looking up at all the work to do, and the potential future we’re shaping with every hesitant cut.

There’s some other tree magic I’ve heard tell of before: whacking the trees with a stick to wake them up. This is performed a little later in the season, around bud break, and a very knowledgeable neighbor of ours, Stan Hildebrand, was a proponent of this technique. Stan knew a lot of things about, well, a lot of things. One thing he really knew about was sorghum syrup. I recently published an article about sorghum syrup, and as happy as I am to have my work presented so professionally and by such a prestigious publication as Saveur, they chose to narrow the story away from Stan and Sandhill and focus more on the present story. As a stand alone story, it’s pretty good. Maybe I’ll tell the rest of it here in the Almanac.