Hardpan, Taproots, and Domestication

Breaking the old scars, growing the new world

The chickadees are back, strutting along worn hedge twigs on their sinewy little claws, nipping at the globby strings of frozen hog fat that I’ve flung over the thorny branches of the mother tree up here on the hedgerow. Today I am 40. There was no breakfast in bed, no moment of repose, just the standard 5 AM awakening beneath my sparse comforter, followed by the immediate need to evacuate my bowels. Unlike most folks living in the affluent Western world, I am largely housebroken, and perform my most necessary functions in an outhouse, dashing over crackling, icy leaves in the darkness towards the creaking, windy doorway of the cramped privy, where I have most of my best ideas. This time of year, I tend to work in insulated bib overalls, which shield me from cold wind and sharp brambles throughout the workday, but also prove themselves to be a formidable obstruction while using these facilities. Shivering and alone except my own frosty breath that steams forth in the light of my headlamp, I make my leavings like a good dog and rush inside to brew something hot before sunlight reaches out onto the frozen and frost-drizzled prairie, my long underwear, the elastic blown out, hastily dragged up as I scamper, feet numb on the cold earth.

Fat is flung upon the tree limbs because this is the time when the fat flows freely. When the weather is right, and the days are slightly above freezing, the nights slightly below, I slaughter pigs or goats. I do save most every scrap in the process, but sometimes, lacking a clean rag, find that wiping my hands, hot with blood and slippery with lard, on the rough bark of the old mother tree, makes for a fine offering for birds and squirrels that gather for the evisceration. A glob of fat here or there notwithstanding, I do my best to maintain a virtue of thrift in the work. I save the bladder to case and press headcheese, spend the evening scraping mucus and vascular linings from the intestines for sausages, stuff the purged and cleaned stomach with salt cured ham before aging, and pull the tail from the stock pot to indulge in it’s fine, lip-smacking texture and warming, unctuous taste. In all, each pig leaves behind little more than some bones for the earth, half a bucket of viscera for the poultry, and a few clumps of bristles that a more industrious person could fashion toothbrushes with, if so inclined.

I promised myself that no matter what the weather was on my birthday, I wouldn’t find myself elbow deep inside a dead animal, which has been the trend these past few years. Thankfully it’s too cold today, but I’ll be back at it tomorrow. For now, I do have a bucket of my own intestinal contents to appropriately handle, which will be layered into a steaming compost pile– perhaps the most radical practice of thrift we engage in here, and the one that I perform every day. Without getting too personal, I estimate that I personally fill ¾ of a bucket with humanure and carbonaceous material a week. I have committed to this act of deep recycling for 12 years, or approximately 468 buckets of shit, or 2,340 gallons. An invisible legacy– may it compost quick and hot and harbor no pathogens, may it permeate the earth and feed centuries of soil life, and remain undetected by the relevant authorities.

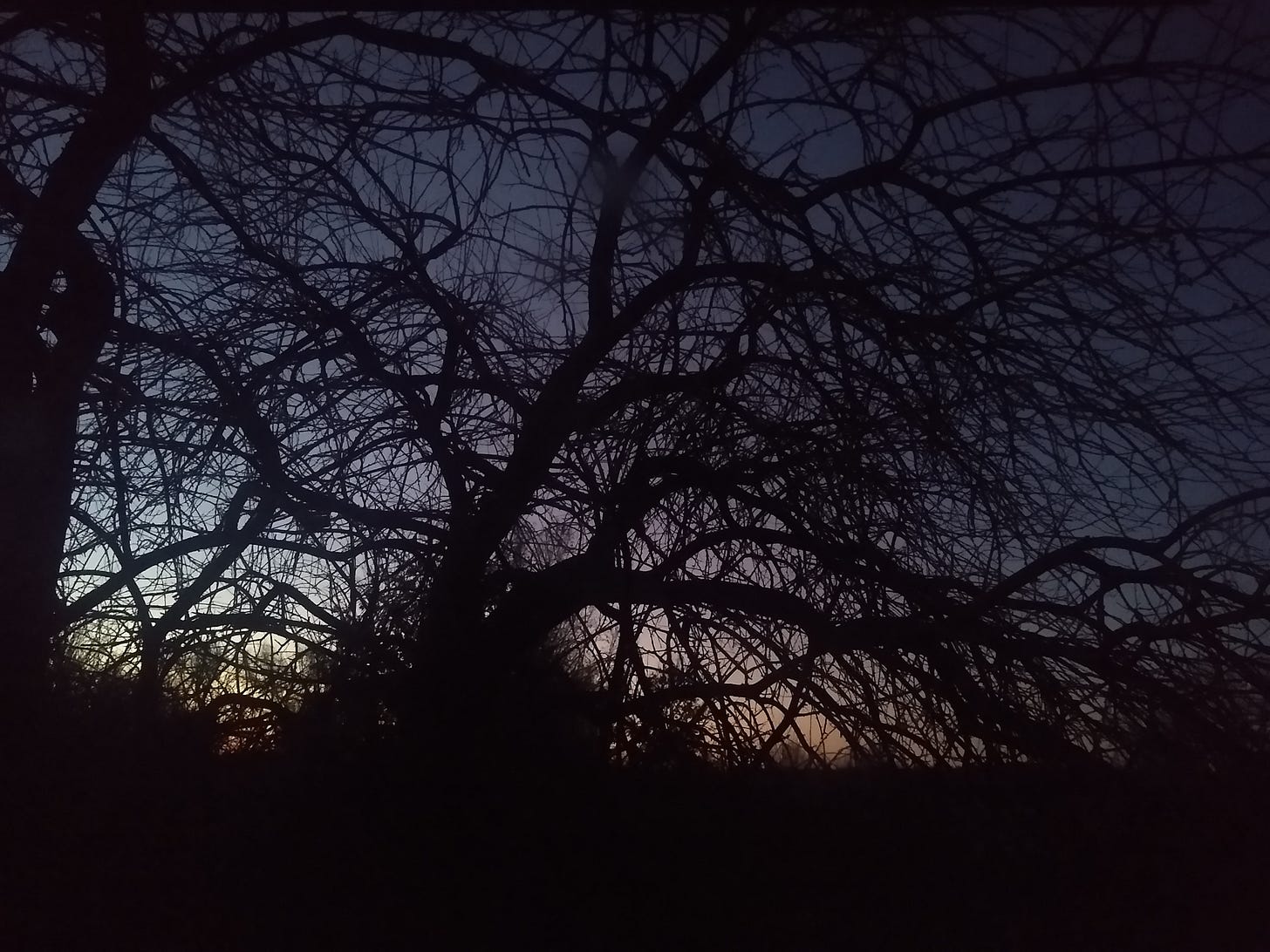

The realization grips me as the darkness of pre-dawn gives way to this day’s earliest shadows, that I have been here, in this work, for more than a quarter of my life, and that life is now half over, give or take. Nearly 500 shit buckets, the only guarantee other than death and taxes, and to be honest, I think I’ll see the reaper well before I’m found out by any taxman. The sun, distant in these solstice weeks, struggles below a formless horizon, where soon, the tired boughs of Eastern red cedar and ochre bones of prairie grass and blow-out ghosts of pale dormant goldenrod will erupt with the mocking call of jays, the harsh scolds of cardinals, and the boisterous play of American tree sparrows. It will glance over the gnarled bark of the old mother hedge, her out-stretched limbs barren of fruit and twisted by decades of wind, split in wounds and fissures from burdens of seed and snow, her young growth spiny, struggling up towards the sun in a darkening landscape. With my guts clear and my overalls pulled on, my bones creak, the old breaks and contusions whining as I slump buckets of grain into the trusty wheelbarrow that has been with me this whole decade, the struts rusted out, the handles bent, the tray rotted through. You and me buddy, we’ve put some miles on.

The land I steward is perched upon what is called hardpan– a concentrated layer of clay, located at plow depth, the ravages of colonial-industrial agriculture. Roots find it hard to penetrate this compacted layer, and often languish upon meeting it. Prairie grass, over time, may break through, and in the process of being grazed or mowed, sloughs off parts of its rootmass, gradually chipping through, laying traces of carbon, of fossil sunshine, through the dense strata of terra cotta. In decades, or centuries, it might be repaired, as organic matter and soil life route through the armor, not that there’s any indication that the world of flora and fauna underlaid by this prairie earth for the past 10,000 years will in any way resemble what comes into being after the hardpan finally crumbles.

I worry about the roots of all the trees we’ve planted becoming stunted, worry that they cannot find their way through the hardpan. Most of our temperate nut trees –oak, chestnut, pecan, hickory, walnut– are reliant on a deep-reaching taproot. I had the option of running a subsoiler or chisel plow to break the hardpan during establishment, even if it was a remote option (I could not find anyone willing to loan me these implements, nor a tractor powerful enough to pull them, but could have kept trying), and I ultimately decided that in spite of the high stakes and costly investment, it would make more sense for me let the silence remain, and reduce soil disturbance and penetration to a minimum. Daily I walk the dogs past all our trees, hoping to keep the predatory white-tail deer population nervous with their scent, seeking any sign that the dormant trees are thriving or failing. I won’t know for some time, I suspect.

Hardpan (or plow-pan, or claypan, depending on your regional vernacular) is a challenge for taprooted trees for a few reasons. Water has a difficult time infiltrating it, and in abundantly wet weather, the roots can become waterlogged, stangnating in the subterranean puddle, and vulnerable to pathogens like phypthoric root rot. The soil’s deeper reserves of mineral nutrition can become difficult to access, and in drought, the trees can struggle to tap into the low-lying lens of soil moisture. I have seen trees thrive moderately well in their first few years and then remain stunted as they bump against the hardpan. In both watering and fertilizing, there is some balance between giving plants what they need to survive, and teaching them to reach deeper for their own long term benefit. I have not figured out how to achieve this subtle equilibrium in all cases.

While the sparrows and chickadees flit about in the cold wind of the bare limbed hedge tree, dancing as they pick apart icy globs and strings of lard, dropping the hulls of sunflower seeds at the firm roots of the stately being that stitch their way through frozen clay and trampled sod and deep earth scarred by plowshares, I think of the most successful trees I know here– the flexible, tenacious Osage orange, the determined honey locust, the shallow-rooted yet opportunistic red cedar, and the pin oak which seems to thrive by the sheer reproductive prowess of its strategically nutritious seed. Wherever the seeds of these species sprout, their roots either find a way through the scar-tissue in the soil, or survive without requiring such deep reserves.

My own roots, after all these years, seem to have found their way to the hardpan, and I do not know if they will continue to feed me, or wither and rot in the struggle for deeper nourishment. But to restore a place like this, we need more roots running deep– living or dead, as pathways for fossil sunlight, food for the ambling world of microbes, a link between what we’ve destroyed and the world of repair we hope to create.

On a walk, the little day-to-day miracles of life above ground reveal themselves, when I am able to see them. A widening woodpecker hole in an old fence post has been carved and chipped open into a diamond shape that seems to harbor three Eastern bluebirds. The shifting, cracking skin of ice on the pond chirps and sings across the dormant basin as it heats in the sun, a haunting, resonant moan that rings out, only heard by a few sparrows. The wind sends loose a squirrel drey from the tippy top of an old pin oak, and I have the rare chance to inspect it up close– it is woven, coarsely, with nibbled twigs, studded with acorns, the leathery leaves surprisingly thick and soft and greenish, the twigs perforated with cicada scars from earlier this summer. I find soft soil here, receptive and unharmed by compaction, a welcome home for deepening roots.

Still, the wild places are few and somewhat fragile, and while they offer comfort and wonder, I can only offer in return some light stewardship. As a domesticated human being, I understand my place is not in the embrace of wilderness, but upon the hardpan, reckoning with and healing what my kind have done, and preparing softer soil for a world quickly careening towards unrest, catastrophe, and extinction. My roots may thrive, or they may rot, but not before breaking their way through for the next succession.

Night sweeps in swift and early, daylight’s final embers burnt down to ash and coal, and the coyotes begin their songs as they close in on cottontails and abscond with the husks and carcasses of fallen deer. Their laughter is abrupt and untamed, and while our mature working dogs pace the edge of their territory and project back a volley of gruff barks, my pup takes on a concerned and fearful posture, whimpering. I too, find myself a bit weary, a bit fearful… forty years of domestication will do this. The foraging birds of the field have returned to their roosts on the rough embrace of thorny hedge-wood, and retreating from the field and the wood, I repair my creaking body near the stove-heat. There’s cake tonight, and I’ll admit that being housebroken and domesticated has its perks. I drive my taproot a bit deeper, and hope to feel a pathway split between the hardened scar tissue of the past. Tomorrow brings little certainty, besides death and shit buckets, but my tax liabilities are likely minimal.

Birthday Blessings to you on this special milestone. May your taproot flourish in the decade ahead. Beautiful writing as always.

Adding "drey" to my word hoard. Thanks for helping future me impress my friends and neighbors!