Vernal Anxiety

Chaotic meanderings and uncontrollable avulsions

Like it or not, it’s spring and I cannot postpone or delay the sprouting, blossoming world any longer. The morning was all snow and rain on the Nanking cherry blossoms, hogs grunting and barking in the icy mud, and robins probing the thinly crusted sod for unfortunate frozen worms. Our hemisphere wobbles into the light– cotyledons unfurling, root hairs penetrating, the wet duff consumed by microbes and fungi and squirming maggots. The plaster of frozen rain has slid off the bursting willow buds in the persistent wind, the wind that sweeps through the open barn doors and past the playful gangs of goat kids that clip-clop along the timber sill– hoof, bone, hide and spirit borne of grass and browse, unfurled and unfurling again in the sudden hue-shift of waking pasture.

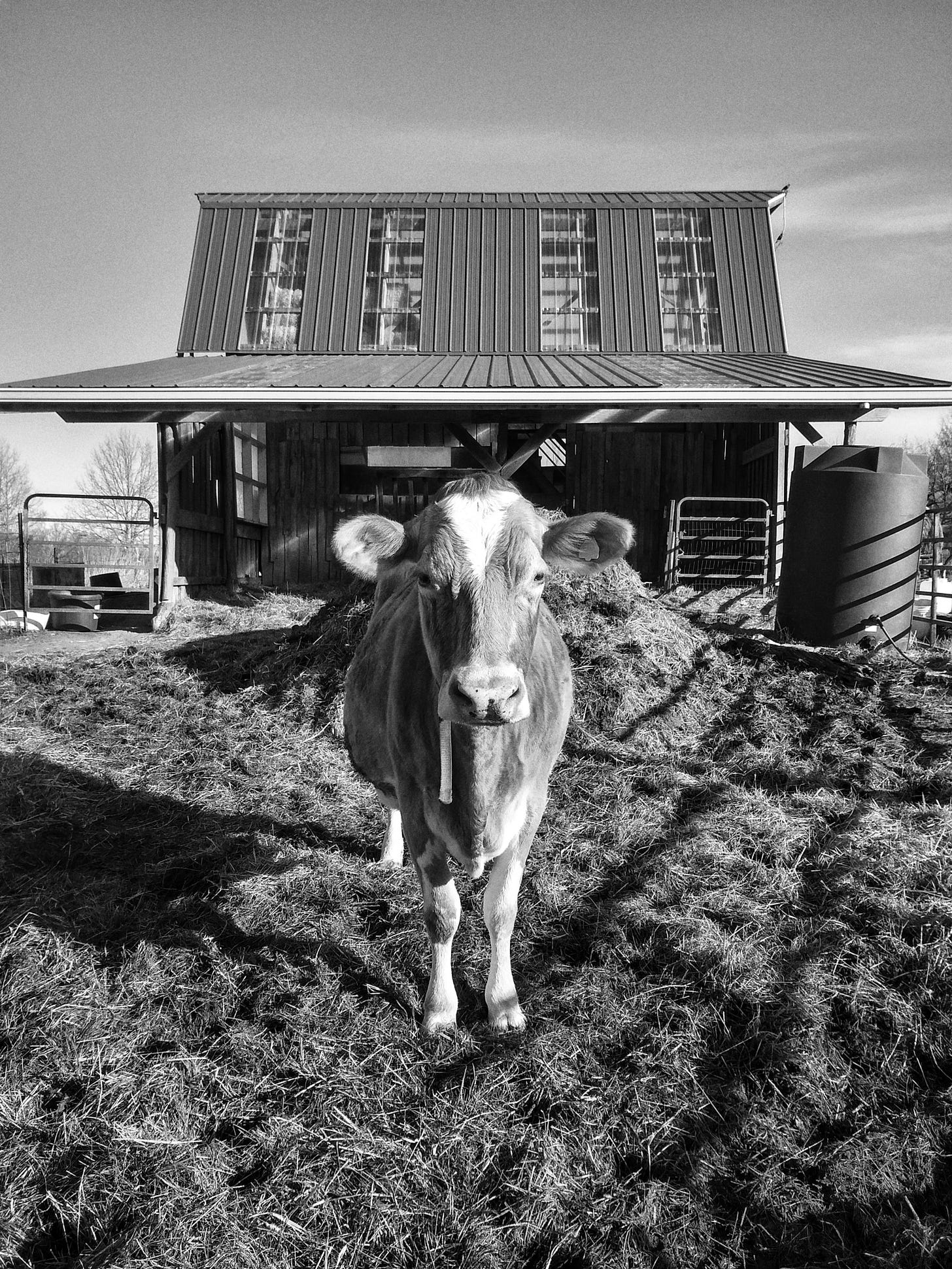

Strong winds have continued to deposit rootless dust from Oklahoma and Texas onto our fields here in Northeast Missouri, the fine earth clinging to condensed water droplets and spattering us with western mud. As the murky drops hit, I stroll the pastures and note how the water runs, where the earth is well-armored against erosion and where it is bare. With each volley of dusty rain the earth trembles, grows sodden. The cows stand at the fence-edge of their loafing yard and inhale grassy air and petrichor– it won’t be long until green up now, and so begins another season of observation, stewardship and careful management.

I’m at the fence-edge too, entering into another year of unknowns. Will it be hot and dry? Will we have enough hay, enough forage? Will I be trucking water tanks to far-flung fields to save newly planted trees? Will avian influenza kill my flock? Will the bottoms flood, choked with mud and debris and drown the hickories and pecans? Will we lose our CRP contract and be forced to somehow monetize this sleeping prairie? The spring is a season of uncertainty– all frozen honeybees trapped under frost clinging to wind torn-willow flowers, verdant rye emerging from overnight snow, wilting heat and waking ticks and western rainbows at sunrise.

I’m a long time, consummate sufferer of vernal anxiety. The unfurling of dandelion buds and yellow-green tips on popple and willow is reflected by our own human implements that spread and scatter over the landscape– farflung shovels and abandoned trowels, buckets of fermenting woodchips and waking tree seedlings lie scattered in the shade of field edges, torn row cover billowing and whipping in the dust and wind. As the air-masses clash and the thrust and pull of currents cause the sky to swell in blooming thunderheads I run in spirals, retrieving pruners and loppers and grafting tape, chainsaws and axes and small, important drill bits from the tops of muddy pallets and PVC barrels that rock and sway in the coming storm.

I am operating out of at least six notebooks– two steno pads, one composition book, and three pocket memos, their pages scrawled by dysfunctional ballpoint pens, the paper silky with fine clay dust and wrinkled with dry sweat, their spines crushed. Their contents are organized in no particular manner, and always seem to lack the crucial information I thought they held when I finally find them. Most of my favorite pants have holes in the pockets, and so access to pens and pencils is ephemeral– all I can ever find are the ones that haven’t been thrown out yet. With or without these tasks lists I understand the essential work of spring– plant what should be planted when the conditions are appropriate, leave nothing halfway finished, maintain what should be maintained when downtime arrives, and do not be fooled by weather predictions or my own plans for a smooth season. Sometimes, standing in the dirt and ticks and wind, I attempt to reference my scrawled lists and a chaotic gust will sweep across the slope and send my crumbling pages of important words into the deep thatch and razor-lined brambles of the field, like wild plum petals.

Meanwhile, the goat barn is full of bleating, wiggling, pouncing life. Watching a dozen and a half or so goat kids can be great entertainment on the fair-weather days when the nannies laze and ruminate in the bird-chirp stillness of spring warmth. It is youth, vitality, rejuvenation– a perfectly marketable damned portrait of this bucolic life, the type of image folks hunger for in this larger season of uncertainty. Contrast this with the actual work of husbandry– intubating weak and screaming kids in the middle of the night, assisting with retained placentas, finding and chasing lost kids in oncoming storms as they scream out from the tangled chaos of thorny rose-bush while unsecured roofing tin trembles like the hair-trigger blade of some aerial guillotine, the unyielding wind washing over the bottomlands, bending limbs and leaving the earth littered in the shattered budshells of pendulous elm blossoms. Springtime kidding does make for some sweet picture postcards– but even the most responsible and caring herdspersons will find the limp and dull-eyed form of dead kids, from time to time.

Thus far, our new herd of little goats has been healthy– thickly framed, bright-eyed and rambunctious, the way we like them. Most of my at-home veterinary care has lately been directed at our tom turkey Jellybean, a beefy Narragansett stud, who while beautiful, is like many male animals at mating season– an asshole. Every morning that I walk down to the poultry yard to care for the birds, he is usually waiting at the gate, booming and strutting and spitting– prepared to defend his hens and look really good while he’s doing it. If my dogs rush in for morning pets he will gobble and chase them, terrorizing these beasts that are five times his size.

I’ve dealt with aggressive tom turkeys before, usually with a nice brine and some slow roasting. While Jellybean hasn’t turned as mean as that, my general observation has been that toms grow more aggressive with age, and his days as ruler of the roost are likely limited–I do not take kindly to thirty pounds of feathers, claws and hormonal aggression flying towards my face every day. Still, Jellybean has a few important jobs to do over the next couple of months– namely breeding hens and protecting them.

A week and half ago, Jellybean did not greet me with his usual display at the poultry yard gate, and I soon found him crouched and pale, with a deep gash on his forehead that left his skull exposed, one eye shut with crusted blood and pus, alive but no longer prideful, a king without his crown. I do not know what got him. I ran and got some help and got him cleaned up and covered in anti-sepsis spray and antibacterial ointment, and expected to have to put him down later that day. This would have been the end of our turkey program for the year.

This year, I’ve decided to not rely on mail-order poults for our turkey project– between the threat of bird flu and the recent unreliability of our postal service, plus the incredible amount of labor required to raise motherless turkeys, I’ve opted for natural brooding. Our heritage turkey program is my pride and joy, and one of the few profitable ventures on this farm– so long as I don’t account for my own labor, and yet I’ve been sitting on the fence about it since last December, uncertain if I could handle another year of the intense workload required to keep my flock moving. By my figuring, if I’m unable or unwilling to herd these birds, a more natural solution is to let the hens –with the help of Jellybean– do the work for me. It is a plan that allows for little control, only care and stewardship. There is a considerable risk that I’ll have no turkey to sell this fall.

I have admittedly been slow to warm to spring, to its toil, to the long days of planting and grazing and struggling in the squirming, living world, but by degrees, I’ve been regaining some of that lost momentum. Despite his sometimes difficult personality, I needed Jellybean to survive. Daily, we caught him and restrained him with a towel, kneeling in the shit and mud, clutching his swollen, nodding head and force feeding him milk. He wouldn’t eat, drink, or dance, but gradually he has been healing. Yesterday, he took his first bites of feed, and this morning he was back at the gate, strutting and spitting and presenting himself to the hens. Jellybean and I are ready for spring at last.

In spite of my attempt to steward natural systems, including their inherent chaos, practicing agriculture still comes down to some attempt at control. I cull and prune, till and modify landscapes, build fences and direct livestock to the right place at the right time, until the clouds of untimely storms billow and boil at the horizon, and the thatch stirs, and the boughs of maples snap and shatter with blowing gusts of dirt-laden wind. Down the road they’re pulling tanks of anhydrous ammonia into bird-less, bug-less fields before the next rain. The sprayer rigs grind along the tilled bare dirt, smelling like old piss, the fine hygroscopic spray magnetized by soil moisture, the plowed out prairie treated like some inert medium to hold carefully calculated applications like a meaningless sponge, every inch and acre processed in this manner to provide the requisite materials for fuels and lubricants and to some small degree– food.

But this place, these fields– they’re not some blank slate for men and machines to impose their control. They have their own will –the roots of horseweed and ragweed that resist herbicides, drawing their strength from deep below the plow-pan and into the long-buried remnants of bison and mastodon, the unbudging glacial erratic boulders that cannot be torn out by tractors or even blown away by dynamite, and the untamed wind that holds the dust of dead fields, come to flatten the corn. Regardless of how it affects us, each spring is growing more wild and chaotic– air masses clash, dams burst, fields burn, and the river always finds its old course. So I am seeking to control less and less.

Back at the fence-edge, our cows can smell the growing grass. We like to wait until the grass is growing fast enough to soak up the soil moisture before grazing, allowing the fragile skin of the earth to stand firm against their hooves. With wet boots I tromp into the most likely first paddocks and grasp at the growth– a cow tongue and a human hand are close in size, and if I can tear off a bite with my hand in a mitten like formation, then the cows can graze it responsibly, not taking it down to the dirt. We’re not there yet, but it’s inevitable. As the earth lies speckled with tools and blossoms and wind-ripped buds I take short, anxious breaths, flavored with old piss and Texas dust. The kids are bleating and playing in the barn and Jellybean is dancing and gobbling, and much work has been left unfinished.

I tromp further downslope to the Long Branch creek, running slow but a bit higher than the day before, where the gobbles and moos and bleats fade and the chorus of croaking peepers overtakes the world of abandoned tools, blowing buckets, and field maps. A big sycamore has been shattered by the gales, its crown splintered and twisted and hung up in its own embrace, swaying in the storm winds. A dead elm has sprouted two turkey vultures that fan themselves out and wait for the drizzle to subside. Fat woodcocks rocket up and out of the shelter of slumping cedars. A notebook page disintegrates in the mud and duff. I crouch at the muddy banks, rooted with walnut and dogwood and old honeylocust, breathe deeper, and wait for the water to find its ancient course again.

Once again, Ben, your words create quite an image!!

So did you have to put Jelly Bean down last year or did he pull through?